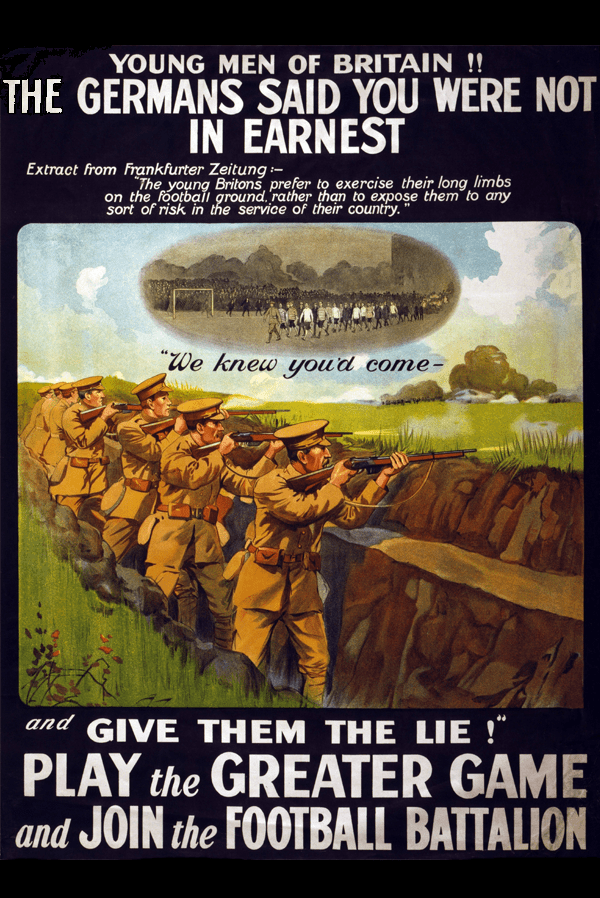

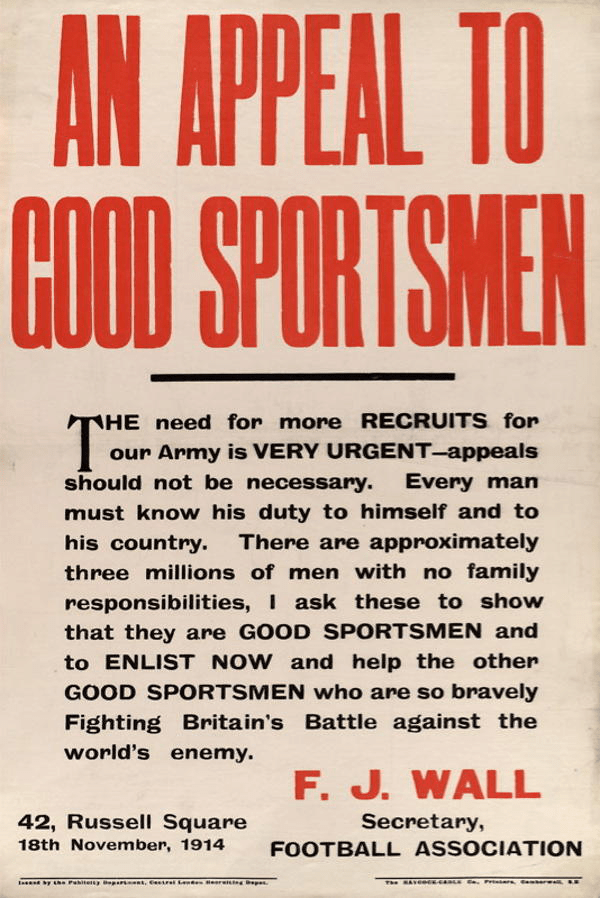

Sporting imagery in World War One recruitment posters

By Medina Macpherson

Image permissions kindly granted by Iain McMullen, ‘Football and the First World War’ project. https://www.footballandthefirstworldwar.org/recruitment-posters/

Upon taking the module ‘Empire, War and Popular Culture in Britain’ in my final year at Loughborough University, I became interested in the idea of conducting a research project using methods drawn from a ‘history from below’ approach. This historical approach shifts the focus of historical analysis from traditional narratives centered on powerful individuals, elites, and major institutions to the perspectives and experiences of ordinary people. This was a key concept in this module as we paid significant attention to the Porter Vs Mackenzie debate regarding popular imperialism – in particular, thinking about how ‘big’ ideologies (like imperialism) might affect ordinary people in their everyday activities. Whilst Porter argued that British imperialism did not have a huge effect on ordinary civilians in the United Kingdom, MacKenzie argued that Empire mattered to British metropolitan life. By adopting a history from below approach, MacKenzie demonstrated examples of how jingoism was able to become embedded in various different sites of popular culture.

***

This debate was a key element in my coursework task which sought to explore the effect that the British Empire had on Victorian and Edwardian popular culture. I decided to use the history from below approach in order to evaluate how and why the general public were inspired through popular culture to support World War One. Using World War One recruitment posters as my main source base, I analysed how sporting imagery was used to encourage enlistment. This tied in with the overall theme of empire and popular imperialism as I argued that sporting imagery was key to promoting Britain as a morally fit nation – a concept that coincided with imperial ideology – and could draw from sport as an everyday experience that people would have been engaged in.

I decided to focus on sporting imagery in recruitment posters for numerous reasons. Firstly, it is a commonplace factor in time of war that governments and societies turned to art and propaganda to rally support, spread messages, and encourage unity among their citizens. This was especially the case at the outbreak of World War One, which makes it a plausible case study for evaluating the effect of Victorian and Edwardian popular culture. Because sporting imagery was central to an imperialised popular culture prior to the outbreak of war, I thought more could be said regarding sporting imagery in recruitment posters because a lot of the research I read had focused on imagery of family, workplace, or the enemy. Imperialism had held up an image of ‘fitness’ to children before 1914 in education, child health, and the Scouts, as well as sport. Some of those children would have been old enough to sign up in 1914: so how were ideologies learnt through physical exercise also present in WW1 recruitment posters?

Sports such as rugby and cricket became defining factors of British teamwork, stoicism and might after being introduced into public schools in the late nineteenth century. In addition, imperialist sentiments were bolstered by the idea of “muscular Christianity” and the belief that sports, particularly team sports, helped build character, discipline, and camaraderie. Sports were thus intended to be representative of national pride and prowess, creating a sense of unity among the British population. Lastly, the timing of World War One and the emergence of sporting imagery is of importance. At the start of the twentieth century, Britain’s international power was challenged by newly industrialising nations with growing militaries such as Germany. My research into the sports-oriented recruitment posters certainly showed how sporting imagery helped to build upon ideologies of fitness and camaraderie, highlighting how fit men equated to a fit nation. Indeed the language of sport and war often became synonymous. As Robert Macdonald (1994) states: ‘the metaphor of war as sport – and its corollary, sport as war – was a commonplace in late nineteenth-century upper middle-class British culture’ (p. 20).

Throughout my essay, I looked at how different recruitment posters made links between the war and different sports, reaching the conclusion that sporting imagery had the ability to appeal to men which resulted in increasing the likelihood of their enlistment. This was due to the previous implementation of sporting rhetoric in daily life prior to the war. When the outbreak of war occurred, war was viewed by some as a game rather than a daunting experience, encouraging those that were already familiar with sports to enlist. Ideas of teamwork, fitness, graft, and working collectively for a cause were central messages communicated by the posters. Ultimately, through posters, the appeal of sports helped to blur many anxieties about war by depicting the war effort as a ‘greater game’.

I used recruitment posters from both the websites: Imperial War Museum and Football and the First World War as my primary source base. Terms like ‘play the game’, ‘join the football battalion’ and ‘fit man’ were commonplace in posters. This not only underlines the link between sports and war, but it also reveals turn-of-the-century ideals about imperial patriotism. Alongside this, I used secondary sources that focused on the languages of the empire, muscular Christianity, and the link between sports and the military to explain how sporting imagery linked directly to imperial sentiments by revealing that it was a common motif used in popular culture before the war.

Overall, my essay aimed to explore the effect that the British Empire had on Victorian and Edwardian popular culture by evaluating the link between sporting and World War One recruitment posters. As a result, I could make links between sport and empire, answering the wider question of how popular culture was used to promote imperialism and a pro-empire rhetoric.

About me:

I have just graduated from Loughborough University, completing my undergraduate degree in BA History (2020-3). My love for history was developed further during my undergraduate degree, especially as I broadened my historical knowledge through the varied and unique modules that the department had to offer. I have particularly enjoyed learning about modern history, especially American and Russian history. This led me to focus my dissertation on Stalin’s infamous cult of personality, which combined elements of Cold War history, Media history and Russian history together.

These are the websites I used for posters:

- “First World War Recruitment Posters”. Imperial War Museum. August 4, 2023. https://www.iwm.org.uk/learning/resources/first-world-war-recruitment-posters.

- “Recruitment posters.” Football and the First World War. August 4, 2023. https://www.footballandthefirstworldwar.org/recruitment-posters/

These are some of the secondary sources I found useful:

- Beaven, Brad. Visions of empire: patriotism, popular culture and the city, 1870–1939. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2012.

- Donaldson, Peter. Sport, war and the British: 1850 to the present. Oxford: Routledge, 2020.

- Macdonald, Robert H. The language of empire: Myths and Metaphors of Popular Imperialism, 1880–1918. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1994.

- Riedi, Eliza and Mason, Tony. Sport and the Military: The British Armed Forces 1880-1960. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Veitch, Colin. “Play up! Play up! and Win the War!’ Football, the Nation and the First World War 1914-15″. Journal of Contemporary History Vol. 20, No. 3 (July 1985): 363-78. Accessed December 12, 2022. http://www.jstor.org/stable/260349

- Watson, Nick J. “Muscular Christianity in the modern age ‘Winning for Christ’ or ‘playing for glory’?”, in Sport and Spirituality, edited by Jim Parry, Mark Nesti, Nick Watson, and Simon J. Robinson, 80-94. Oxford: Taylor & Francis, 2007.

Students as Researchers

Innovative Undergraduate Research in International Relations, Politics and History