The Figure of the “Mad Scientist” and Victorian Attitudes to Science and Religion

By Jasmine Cairns

I am currently in my second year of History (BA) at Loughborough University. I’ve always had a fascination with the past, but it was during my GCSEs that a particular teacher changed the way I saw the subject: History isn’t just a study of what was, but a warning of what could be again- a reflection of our own capabilities for courage, cruelty and change. Studying at Loughborough thus far has further compounded this sentiment, helping me appreciate not just the what, but the how and why, transforming my view on the world around me, and shaping me into a more thoughtful and perceptive individual.

One of the most, admittedly unexpectedly, eye-opening modules I have taken is Dr Peter Yeandle’s Victorian Values Reconsidered. While I came into it expecting crinoline skirts and stiff upper lips, what I found instead was a period in crisis – grappling with change, anxiety, and the promise (and threat) of progress. Sound familiar? Nowhere was that tension clearer than in Victorian attitudes toward science, and how these were expressed through the fascinating figure of the “mad scientist”, a cultural phenomenon both feared and revered, and the focus of my coursework essay “How did the figure of the mad scientist reflect Victorian attitudes around scientific developments?”

***

We often think of the mad scientist as a wild-eyed figure in a lab coat, tinkering away with lightning and test tubes. But this trope didn’t come out of nowhere – it is rooted in the nineteenth century clashes between rapid scientific development and religious belief, moral certainties and doubt, and challenges to traditional views of authority. The mad scientist, I’ve come to realise, was not just a character. He was a cultural warning sign.

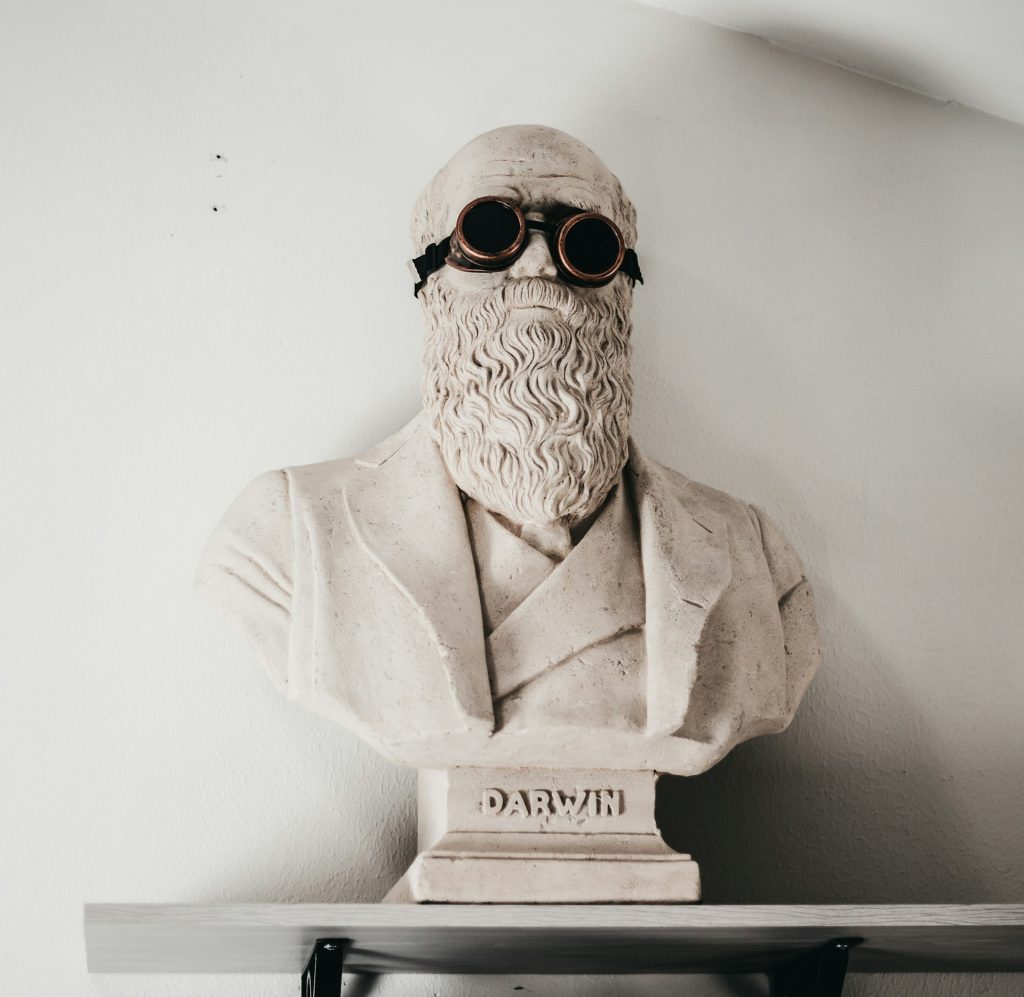

Take Charles Darwin, for example. Today, he’s remembered as the father of evolutionary biology, a groundbreaking mind. But when On the Origin of Species was published in 1859, Darwin’s theory of natural selection was seen by many as nothing short of heretical. It flew in the face of the biblical story of creation, prompting outrage and ridicule. To many Victorians, he was a dangerous figure – someone who had “played God” by daring to question divine design. The reaction to Darwin helps explain why some eminent Victorians came to see some scientists as “mad”, not necessarily because they were mentally unstable, but because they crossed the moral and spiritual boundaries that society wasn’t ready to let go of.

That fear wasn’t just centered around real people, it was fictionalised, too. When brainstorming ideas for my essay topic, it was Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886) that kept reappearing in my mind. Stevenson’s depiction of Victorian society formed a large part of my understanding of the era prior to this module, and the novel tackles a plethora of themes: science, religion, human nature, and social responsibility, and so on. The line between genius and madness is explored dramatically in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. A well-respected doctor, seeking to separate the good and evil within himself through science, instead unleashes Hyde: a creature of primal violence and immorality. Hyde’s “ape-like fury” and “troglodytic” nature reflect Darwinian language, hinting at humanity’s animal instincts lurking just beneath the surface. Jekyll’s fate is similar to other more contemporary “mad scientists” (think Dr. Connors in The Amazing Spider-Man and Dr. No in Dr. No). He is destroyed by his own creation, not because science is evil but because he pursues it without restraint or empathy.

I also explored Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. This iconic work, though originally published in 1818, gained a renewed audience in the Victorian period, and its message was clear: scientific ambition without responsibility is dangerous. The Protagonist, Victor Frankenstein, literature’s first “mad scientist”, embarks on a blasphemous venture to replicate the role of God: to create life from death. His desire to “bestow animation upon lifeless matter” sounds impressive, until you realise the monster he creates is unloved, rejected, and ultimately turns to violence. Victor became absorbed by ego and unchecked ambition, and like Prometheus – referenced in the novel’s subtitle The Modern Prometheus – he is punished for defying the natural order.

The tragedy of Frankenstein is a warning for overstepping the boundaries believed set by God; the scientist’s downfall encapsulates Victorian fears of science as a disruptive force when untethered from moral or spiritual guidance.

That fear deepens when science seems to shrug off morality altogether. In real life, the story of Dr. Robert Knox – an Edinburgh anatomist linked to the infamous Burke and Hare murders – is a chilling case in point. Knox purchased cadavers from the two men for medical dissection, turning a blind eye to where they came from. Whether he knew they were murdered or not, his “clinical detachment” terrified the public. Knox embodied the stereotype of the cold, obsessive scientist, willing to forego ethics for the sake of discovery.

What I found most interesting when building my essay was how Victorian-style fears still linger in our culture today. The mad scientist remains a powerful image – from horror films to superhero stories – and it always comes back to the same questions: Should we do something just because we can? What happens when we value knowledge over ethics? And who decides where the boundaries lie?

In the end, the Victorian “mad scientist” was less about actual madness and more about moral panic. These figures represented a society trying to come to terms with massive change, unsure whether science would save them or destroy them. It’s a dilemma that still feels relevant today – in the age of AI, genetic editing, and chemical weaponry, we’re still asking: where does progress end, and hubris begin?

Some recommended reading:

Novels:

- Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft. Frankenstein: or the Modern Prometheus. London: George Routledge and Sons, 1891 edition.

- Stevenson, Robert Louis. Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. London: Longmans, Green, and Company, 1886.

Secondary Sources:

- Goodall, Jane. “Electrical romanticism.” In Frankenstein’s Science: Experimentation and Discovery in Romantic Culture, 1780-1930, edited by Jane Goodall and Christa Knellwolf, 117-132. London: Routledge, 2016.

- Sanders, Elizabeth M. Genres of Doubt: Science Fiction, Fantasy and the Victorian Crisis of Faith. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2017.

- Toumey, C. P. (1992). “The Moral Character of Mad Scientists: A Cultural Critique of Science.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 17, no. 4: 411-437. https://doi.org/10.1177/016224399201700401.

- Weingart, Peter, Claudia Muhl, and Petra Pansegrau. “Of power maniacs and unethical geniuses: Science and scientists in fiction film.” Public Understanding of Science 12, no. 3 (2003): 279-287.

Image by: Logan Gutierrez on Unsplash

Students as Researchers

Innovative Undergraduate Research in International Relations, Politics and History