Playing for the Planet: Sports Greatest Game

In sport, human beings and the natural world come together as competitors and partners, an athlete’s relationship with the natural world is raw, passionate and physical.

Nature and sport are inextricably connected and nature’s role can be decisive in the outcome of an event. The greatest tournaments and events rely on energy, infrastructure and resources to be successful. Therefore, it is vital sport plays a role in protecting the natural world it so heavily relies on.

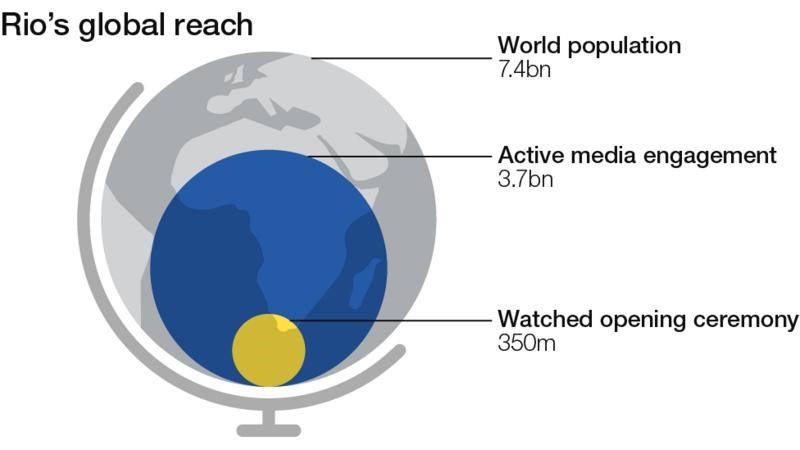

All of us have experienced sport at some point in our lives. You might have been the overly competitive kid at school like me, perhaps you avoided it at all costs growing up, or you prefer just to watch it from the comfort of your sofa. However, even those with little interest in sport day-to-day usually come together to enjoy the huge world spectacles such as the Olympics or world cups. Estimates vary, but the sports industry is commonly considered to be worth around $1 trillion, with some estimates suggesting as high as $1.3 trillion.

For me, sport is a huge part of my life; it’s one of the reasons I came to Loughborough to study. I’ve also got another huge passion – sustainability. Therefore, I’ve always been interested in exploring whether these two areas should work hand in hand, and questioning, is sport doing enough to reduce its environmental impact?

An often-overlooked issue is climate change’s influence on sports and recreation. Cancelled football matches, flooded cricket grounds, lack of snow on the slopes and golf courses crumbling into the sea – climate change is already impacting our ability to play and watch the sports we love.

Sport is not just a victim of change, however, but also an important contributor.

One thing that cannot be escaped is the commercial beast that is football. It is estimated that European professional leagues are worth €28.4 billion, yet currently only 2% of clubs in the top-5 leagues are signatories of the UN Sport for Climate Action Framework.

The constant strives by both sports brands and clubs to maximise their brands across the world comes at a heavy price. It’s common practise for clubs to release brand new kits before every season, with Man Utd topping the sale charts with an average of 1.75 million shirt sales globally each year…..the city itself only has a population of around 600,000 people! These alarming levels of consumption are not exclusive to football and can be seen in sports like rugby too.

Travel associated with sports teams or events is quite often the largest contributor to carbon emissions. For example the 2010 World Cup in South Africa showed an impact of 2.8 million tonnes CO2 attributed to travel, representing 86% of the total event’s reported footprint. To put this into context we estimate the University produces 15-20,000 tonnes CO2 for business and commuter travel each year!

It’s not surprising that travel has this level of impact when you consider international events. For example, pre-season tournaments like the International Champions Cup see between 15-20 European football clubs travel to the US, Singapore and China to play in friendly games. We’ve also seen the growth of American sports being played in the UK, with London hosting NFL, MLB and NBA games annually. Flying all over the world to play games that could be staged on the same continent and still be broadcast to a global audience seems questionable. As we all know though money talks!!

The Olympics are frequently described as the greatest show on earth, and often seen by governments as a way to bring in investment and create an Olympic legacy for the host country, but what happens when the eyes of the world turns its attention away after the games? All too often these venues can be found unused and in disrepair within months of the hosts celebrating the biggest event in the world. There are even examples of stadiums being built where the capacity exceeds the cities they are located. Surely we need to see Countries demonstrate the viability of these facilities long term before handing over these vast sums of money and the environmental costs that come with hosting these huge events.

However, some sporting events have begun to recognise their environmental impact and have started working towards minimising this or even making a positive impact.

The 2012 London Olympic games were supposedly “the greenest ever” held. It made use of existing venues and the Olympic Park was largely accessed by public transport. Some 86% of Olympic visitors travelled by rail, according to the post-game sustainability report, and 99% of the 61,000 tonnes of waste was either recycled or reused. The London Games stadium wrap, made of hundreds of fabric panels, were repurposed for projects benefiting former child soldiers in Uganda, and for use at shaded community areas at the 2016 Summer Games in Brazil. This a is great example of SDG 12, Responsible Consumption & Production.

Formula One recently announced that they plan to be net Zero Carbon by 2030, this is remarkable considering the whole sport has been built on fossil fuel-powered engines. You may not realise it but F1 has been a pioneer in a lot of technology we now use to reduce our environmental impacts. For example, the hybrid systems present in everyday vehicles and the aerofoil technology used in supermarket refrigerators to reduce their CO₂ footprint were both developed on the racetrack.

Sports brands are trying to reduce their footprint by looking at how they produce their products. In 2015, Adidas launched their ‘Parley for Oceans’ scheme, where they make football shirts, training clothes and trainers using recovered plastic from clean-up operations around the world.

Parley’s strategy is based on three ideas: avoiding plastic where possible, intercepting plastic waste and changing how plastic is used. It takes 11 plastic bottles to make a pair of trainers, with other recycled materials making up the rest of the shoe. Big hitters such as Real Madrid have worn full kits made from recycled plastics. These kind of collaborations between clubs and major sports brands are the positive stories that can make a huge impact. Furthermore, Adidas has also committed to using recycled plastic in all its products by 2024.

It is also pleasing to see most Premier league football clubs are now taking their environmental management obligations more seriously. I won’t go into all the detail but you see here that most teams are engaging in some form of sustainable practises.

Its interesting to bring this topic back to the context of Loughborough. The University is renowned for its world class academics, athletes and facilities and it also plays host to a large number of the UK sports governing bodies. Could we use this unique position to drive meaningful change across sport at Loughborough and beyond? Its certainly something we should be looking at!

Its clear sports are not doing enough, and as the participators, observers and funders of the industry, we can help show we want change by supporting campaigns such as Parley for oceans and demanding better resource management. A survey from Sport Positive showed more than half of respondents (58%) strongly agreed with the statement: “I care about how my club impacts the environment.”

Sport’s status as a beloved entertainment form has perhaps shielded it from the scrutiny felt by other economic sectors. But it is time now for sustainability to play a central role in sport.

Jochem Verberne, WWF international

I believe sport is in a unique position to lead by example when it comes to sustainability. It is something we all encounter at some point in our lives and many of the clubs and individuals act as role models for millions across the world. There can be little dispute about the extraordinary levels of passion that sport is able to inspire and its capacity to cross boundaries and bridge divides is unique. Not many sectors have this ability.

It is in the interest of sports to try their best to reduce their environmental impact, for some sports climate change could be their demise.

Sustainably Speaking

Loughborough University Sustainability Blog