Waste and Recycling: The Bigger Picture

When we talk about waste and sustainability, the conversation should go much further than and never begin with how can we increase recycling. Instead, it requires a complete transformation of how we think about the design of, production of, distribution of, consumption of, disposal of, and just as importantly, our own relationship with “stuff”.

The impact of our ever-increasing demand for “stuff” abides by no boundaries – geographical, political, economic, social, or cultural. Just one example, particularly poignant in the news recently with the case of Boohoo, is fast fashion. I want to avoid poking at the chicken or the egg debate around whether it is our incessant demand, advertising and the “influencer” culture, or our capitalist mode of production as the main driver. Whichever you feel is the main driver, it’s important to see them all as feeding into the vicious cycle of the industry.

They all drive an increasing demand for faster, newer, and ever-cheaper. This in turn drives the mass production of low-quality plastic clothing by huge companies, usually stealing the designs of smaller independent ones. The production, manufacturing, and transportation processes account for 10% of global carbon emissions, drains our finite resources, and make the industry the second-largest consumer of the world’s water supply.

The clothes are usually made by ethnic minorities in conditions reported as modern slavery. They are then plastered on every single influencer on every platform and consumed at a catastrophic rate by the Western world. And yet, their poor quality and fleeting style sees them thrown away or “donated” within a few years. And it doesn’t matter which way they’re disposed of, they will surely be found dumped in developing countries like Ghana, and their fibres found in our oceans.

This is just one example of how the current design, production, distribution, consumption, disposal, and psychology of “stuff” negatively impacts both people and planet. It is not as simple as recycling these clothes, or any other item like electronics or furniture – the entire politics, economics, and culture of “stuff” needs turning on it’s head.

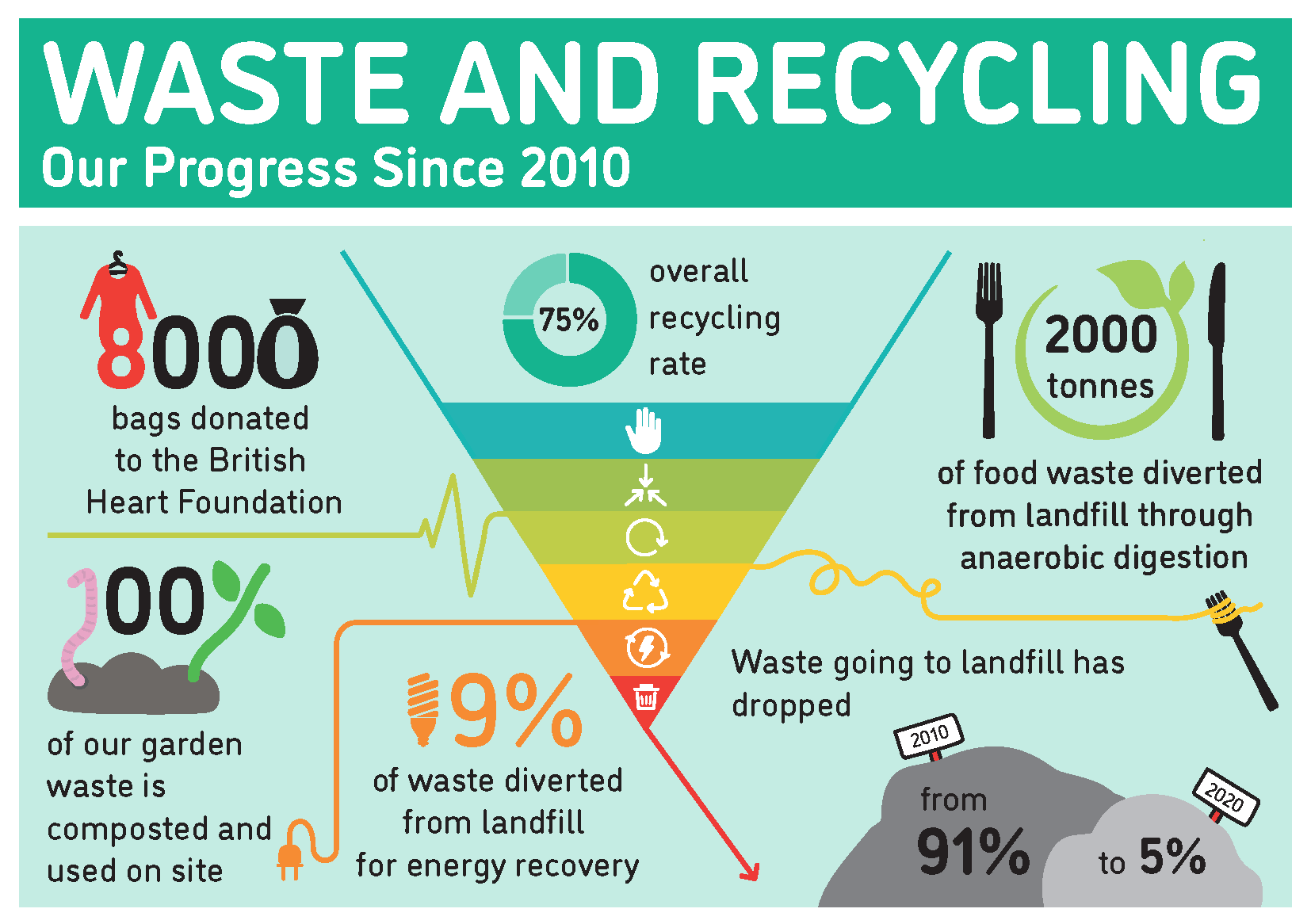

Here at the university, we have a legal obligation to adhere to the waste hierarchy which attempts to start this process. The hierarchy lays out a new blueprint for how and where to start thinking about all this “stuff”, and it does not begin with recycling. Rather, it asks us to begin the process by re-thinking the need for the product. Is this product actually useful? Does it hold a genuine purpose or is it a waste of resources? If the answer is the latter, then we must refuse to buy it, as well as refuse to make it.

In the case of clothing, we have to break out of the habit that just because clothes are relatively cheap and can be “donated” once we no longer want them, this system is still inherently broken. It encourages over-consumption and the over-production of such poor quality clothing that they have next to no-resale value in the countries that donations are shipped to. Furthermore, the sheer quantities (around 50 tonnes a day) means countries like Ghana’s infrastructure are overwhelmed. The result? Our donated items are rotting on landfills and polluting developing countries. Therefore, if we apply the waste hierarchy, we as consumers must refuse to purchase these items and reduce our consumption of clothes in general. In addition, clothing retailers must redesign their clothing to be of higher quality and be more durable.

One example of Loughborough considering this material use value is with polystyrene takeaway containers. In 2017, the University used over 150,000 single-use takeaway meal boxes in student dining halls around campus, and their inability to be recycled meant they all went ended up in general waste. In 2018, the university stopped the use of these containers and introduced the EFB – a re-usable takeaway container for students to purchase at a reduced rate which could be used in all catering outlets.

If a product is useful, then how can it be redesigned in a way to make it more efficient, more durable, more repairable, and at the very least completely recyclable or reusable? How can it be redesigned to utilise waste or by-products, or at the very least not use finite resources like oil? How can it’s production or manufacturing process use less water or land? One great local example of this redesign is the Circular Cup (previously called the Rcup), made by Loughborough alumni Dan Dicker, which is a re-usable cup made from used single-use cups.

However, as I explained earlier, it is not just this “stuffs” material use which needs to be considered. It’s also it’s economic, social, political, and cultural use. When we buy products, whether that’s through university’s procurement process, or as individuals, we need to start asking questions. Is this company known for paying their workers a fair wage? Are the products being made in safe conditions? Has the company been active in it’s pursuit of ethical sourcing and manufacturing? One great example of this is Tony’s Chocolonely, which advocates for a 100% slave-free norm in the chocolate industry, and are now available to buy on campus.

As signatories of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, we’ve made a commitment to reduce our waste and effectively manage our resources, as set out in goal 12. However, in signing the accord we’ve also made the commitment to build a more sustainable community, support industry innovation, and reduce inequalities. Just as I explained in my last blog post, ‘Intersectional Environmentalism: Why it’s crucial for climate justice‘, it’s not simply about the treatment of the environment but how this intersects with the treatment of people. It is in the favour of both people and planet to let go of all our “stuff”.

Read our latest blog posts:

- Solar Panels – are they worth it?

- Have a green Christmas

- Drought warnings for 2026 issued

- Sustainability Blog Guide: Travel

- Sustainability Blog Guide: Water

Sustainably Speaking

Loughborough University Sustainability Blog