What was the UN’s Biodiversity Conference (COP15), and what were its outcomes?

What was COP15?

There are two COP events each year now. The first focuses on climate change and you can read our blog on this year’s COP27 here. The second is specifically on biodiversity (COP15), with this year’s being the 15th meeting of the United Nations’ Convention on Biological Diversity. This year’s two-week COP15 summit took place in Montreal, Canada from Wednesday 7th December to Monday 19th December 2022.

The conference brought together countries from across the world, with representatives from 196 governments, and delegates from a wide range of stakeholders such as Indigenous peoples, academics, scientists, local communities, youth representatives, and people from the business and finance community.

A brief background to the Biodiversity Crisis:

Addressing biodiversity loss is absolutely critical, especially at this stage. The largest loss of life since the dinosaurs, with one million species being threatened with extinction, is underway.

Check out the Living Planet Index, a great metric which was created by the WWF and the Zoological Society of London to measure life on earth. Wildlife figures have dropped by an average of 69% between 1970 and 2018 according to recent studies.

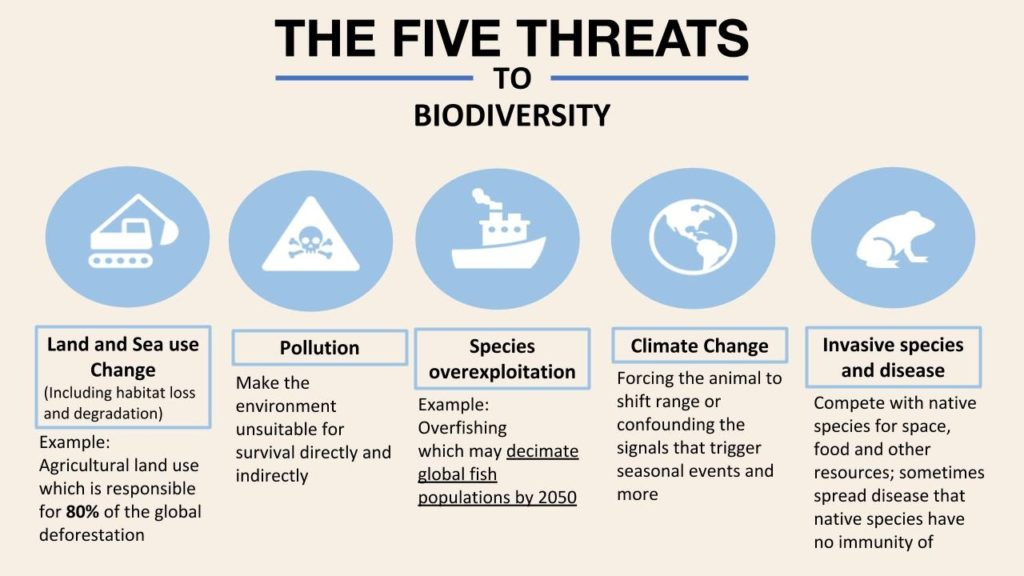

Here is an infographic which shows the five main threats to biodiversity:

What were the main outcomes from this year’s COP15?

I know this is what you’ve all been waiting to know- did the conference actually achieve anything? Well, I’m happy to say that, yes, a landmark agreement was made to guide global action on combatting biodiversity loss. On the last day of negotiations, the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) was adopted, which aims to address biodiversity loss, restore ecosystems and protect indigenous rights. The GBF replaces the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020 and associated Aichi Targets agreed on by parties in 2010. Importantly, almost every nation in the world signed up to this framework!

There are 23 targets set to achieve by 2030 within the GBF, including some which I have split into the following categories:

Conservation, Restoration, and Management

- Effective conservation and management of at least 30 per cent of the world’s land, coastal areas and oceans.

- Restoration of 30 per cent of terrestrial and marine ecosystems. Currently, 17 percent of land and *8 per cent of marine areas are under protection

- Reduce to near zero the loss of areas of high biodiversity importance and high ecological integrity

At Loughborough University, we are lucky to have such an amazing gardens and grounds team who maintain the campus and its biodiversity. The University has an established Biodiversity Working Group who develop and steer delivery of the Biodiversity Action Plan for the whole University. There is also a Woodland Management Group which meets twice yearly and offers an opportunity for external stakeholders to comment on management of the woodlands and contribute their knowledge and advice.

Check out our ‘Support a species’ page for more information on some of the species living in our environment, key facts, some of their threats, and importantly how you can help them.

One key area which comes into this section, is deforestation. It was found by scientists, in 2021, that the Amazon rainforest is now emitting more C02 than it is absorbing. A large amount of these emissions is the result of forest fires, caused deliberately to clear land for beef and soy production. We can see how devastating this is, and the urgent need for change to happen.

As I mentioned in the COP27 blog, the new president of Brazil, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, won against the former far-right president Jair Bolsonaro and has since pledged to save the Amazon rainforest (much of this lying within Brazil) and to end deforestation there by committing his country to reaching net-zero deforestation by 2030. As Bolsonaro appeared largely pro-deforestation, the new president’s goals display a huge sign of hope and change for our world.

Food waste

- Halving global food waste

To put this into perspective, in UK households we waste 6.5 million tonnes of food every year, 4.5 million of which is edible. This statistic has to change for us to meet the targets set within the GBF. If everyone in the UK stopped wasting food at home for just one day, it would have the same impact on greenhouse gasses as planting half a million trees.

Loughborough University segregates its food waste in the majority of retail and all catering operations, as well as providing the opportunity for students to do so in all our on-campus halls of residence. This food waste is then sent for anaerobic digestion instead of going to landfill, saving both money and the environment.

LU also supports the Love Food Hate Waste campaign, where you can find some great food saving tips! Check out the below video (and more here) for some insights and tips.

Finance

- Mobilizing at least $200 billion per year from public and private sources for biodiversity-related funding

- Raising international financial flows from developed to developing countries to at least US$30 billion per year

- Phasing out or reforming subsidies that harm biodiversity by at least $500 billion per year, while scaling up positive incentives for biodiversity conservation and sustainable use

- Requiring transnational companies and financial institutions to monitor, assess, and transparently disclose risks and impacts on biodiversity through their operations, portfolios, supply and value chains

Just an ‘agreement’?

So, as I mentioned in our COP27 blog post, the pledges and agreements made are not legally binding, and countries are not penalised if they don’t meet them. Despite the embarrassment that the countries may face if they don’t meet their pledges, this may not be enough to ensure that the proposed (and critical) action is taken.

This same issue can be seen with the Global Biodiversity Framework, with targets having been set to be met by 2030, but no binding contract for countries to meet them except a ‘pledge’. Concern has been demonstrated here, as nations had previously set Aichi targets at COP10 in 2010 to be met by 2020. Shockingly, the world failed to achieve even a single one of these targets by the 2020 goal, sparking a conversation about how well the COP15 GBF will do (already coming two years late due to COVID as it is). All we can do is have hope though, right?

Here’s a video that shares the thoughts of 10 people on what they believe needs to happen to make the GBF successful:

How has Loughborough University been involved with COP15?

Loughborough University is a proud founding member of the Nature Positive Universities Alliance that was launched on Thursday 8 December at the UN Biodiversity Conference (COP15). This is a global network of universities that have made an official pledge to work towards a Nature Positive goal in order to halt, prevent and reverse nature loss through addressing their own impacts and restoring ecosystems harmed by their activities.

For more information on this, see the University’s article on it here.

A new report, SPORTS FOR NATURE, carried out the first-ever assessment of how sports that take place on landscapes ranging from water, turf, mountains, and cities can act to protect nature. The report was commissioned by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), led by researchers at Loughborough University. The study – which consulted more than 100 organisations representing 30 different sports across 48 countries – assessed what work is currently being done by sports on the global nature agenda and was supported by the International Olympic Committee.

This article is in support of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 15: Life on Land. To read more click here.

Sustainably Speaking

Loughborough University Sustainability Blog