Fashion, Identity, and Sustainability

This is a guest blog, written by Jennifer Agu, who is one of Loughborough University’s Sustainability Ambassadors, and is also studying for a Biotechnology MSc in the Department of Chemical Engineering, Loughborough University.

My enthusiasm for personalization, conscious decision-making, and design came to life as I worked alongside the Production Team for the Sustainable Fashion Show organised by the Loughborough Enterprise Network.

However, it is my Nigerian upbringing and experience studying for a biotechnology master’s degree and my role as a Sustainability Ambassador at Loughborough University that have truly shaped my perspective on the interconnectedness of sustainability and identity.

Now, I am thrilled to share my thoughts and insights on the crucial connection between fashion, identity, and sustainability. Through this blog post, we will explore a world where fashion intertwines with identity and sustainability, uncovering the potential for positive change through conscious consumption.

Fashion and Second-Hand Clothing

Growing up in Nigeria, I witnessed firsthand the importance of fashion as a form of self-expression and cultural identity. This form of fashion allowed for self-expression and creativity while being affordable. However, I soon realized that second-hand clothing was often excess clothing donated by Western countries, which raised concerns about the industry’s impact on textile waste and the exploitation of lesser-developed nations.

Figure 1: One of the most popular second-hand clothing markets in Port Harcourt, Nigeria [1]

Personalization and Identity

My journey in understanding the significance of fashion as a communication of identity became evident when I moved to Loughborough. Pink is one of my mother’s favourite colours and she gifted me a pair of pink Crocs right before I relocated. I wore them a lot as they reminded me of home and made me feel close to her. This sparked my interest in incorporating pink into my identity. I explored various avenues such as learning to style my hair in braids, acquiring a pink wig, collecting a pair of bright pink sandals I saw listed on the Olio app and experimenting with accessories to communicate my inner emotions outwardly.

Figure 2: Pink wig I got at the local Salvation Army, 34 Devonshire Square, LE11 3DW.

Industrialization, Environmentalism, and Social Justice

Witnessing the direct impact of industrialization on my hometown, particularly in the textile production sector, fuelled my ever-growing interest in environmentalism, social justice, waste minimization, and sustainability. It became clear to me that embracing green living practices required self-critique, especially when it came to our consumption patterns. These reflections are even more crucial in the face of the prevailing fast fashion culture.

The Pitfalls of Fast Fashion

Fast fashion’s allure lies in its promise of convenience and affordability, catering to our desire for instant gratification. However, these promises come at a cost. As consumers, we are often disconnected from the design process of our clothing, making it difficult to ascertain the intended use and disposal methods. This is where personalization becomes significant [2].

Figure 3: Pink sandals I got off Olio!

Conscious Decision-Making and Responsible Consumption

Conscious decision-making is a simple yet powerful approach to expressing oneself in a manner that aligns with personal values. It involves distinguishing between wants and needs. Previously, I used to buy bodycon dresses from fast fashion brands for every event, only to realize that the low-quality clothing resulted in both waste and wasted money.

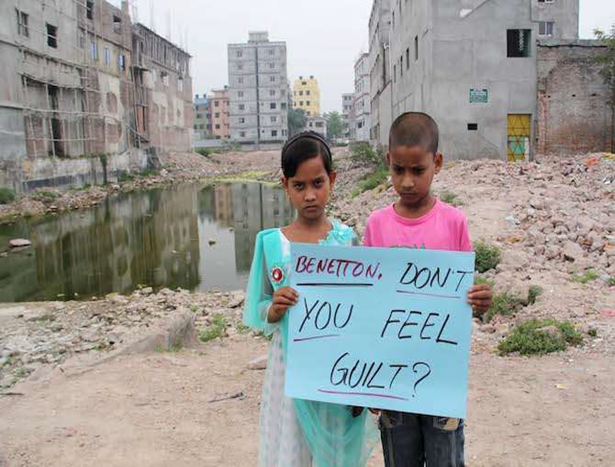

Figure 4: Photo from ‘Inside Out’ campaign that started as a response to the factory tragedy that occurred on 24 April 2013 in Dhaka, Bangladesh[3] Photo Credit: Sebastian Damberger and Fritz Straube, Haar und.

The Impact of Fast Fashion on Global Capitalism and Workers’ Conditions

Fashion, politics, and identity are deeply intertwined due to fashion being historically political. By consuming fast fashion, we inadvertently contribute to global capitalism while impoverishing textile workers in countries like Bangladesh, China, and India, as they endure unfavourable conditions to meet the demands of mass consumption. It is crucial to consider the ethos and treatment of workers by fashion companies and designers, especially in mass-production settings.

Figure 5: Children whose garment worker parents died in the 2013 Rana Plaza tragedy hold a placard to demand justice in this 2015 photo. (Photo by Stephan Uttom Rozario / A long road to justice for Rana Plaza victims – UCA News)

Defining Sustainable Fashion

Defining sustainable fashion can be challenging due to the various interpretations of sustainability. However, a rule of thumb is to consider the value of clothing in terms of reusability, longevity, and fabric quality. By prioritizing these factors, we create opportunities for personalization through upcycling and styling, fostering a more meaningful relationship with our clothes and minimizing textile waste.

Promoting Responsible Consumption

To effectively manage clothes we no longer want, it is imperative to adopt responsible end-of-life strategies. Donating to charity shops such as Loros, the British Heart Foundation, and the Salvation Army is an effective way of extending the lifecycle of garments.

These actions not only contribute to waste reduction but also initiate meaningful conversations about responsible consumption.

Figure 6: As seen in British Heart Foundation, Clumber St, Nottingham NG1 3G.

As we embark on the journey towards responsible consumption and production, let us remember that everyone, regardless of social status, deserves a decent material standard of life. While fast fashion may seem appealing in meeting our immediate desires, it perpetuates a linear economy that disregards the environmental impacts of production and disposal [4].

In a traditional linear economy, resources are extracted, transformed into products, and eventually discarded as waste after their use. In contrast, a circular economy seeks to close the loop by creating a continuous cycle where products and materials are reused, repaired, remanufactured, or recycled to create new value.

To shift towards a more sustainable and circular economic system, it is essential to understand that identity and mindful consumption are deeply interconnected, and as such our fashion choices have the potential to shape a more sustainable and meaningful future.

By embracing sustainable fashion practices, we can forge a more equitable and environmentally conscious future. You can make an impact in the collective action by being part of this Fashion Revolution Week 2024 happening between April 15th and 24th.

Wishing you the best in your journey!

The Give ‘n’ Go campaign is a great way to donate your unwanted garments during the end of year move outs!

This article is in support of UN Sustainable Development Goal 12 ‘Responsible consumption and production’. To find out more, click here.

References

- Port Harcourt People [@AskPHPeople]. (2018, October 12). Important Markets in Port-Harcourt. #PHCity [Image attached] [Post]. X formerly known as Twitter. https://twitter.com/AskPHPeople/status/1050773644337664000

- A. Gwilt and T. Rissanen, Shaping Sustainable Fashion: Changing the Way We Make and Use Clothes. Taylor and Francis, 2012.

- K. A. Plonka, “Inside out – the fashion revolution campaigns for consumers’ awareness of working conditions,” FairPlanet https://www.fairplanet.org/story/inside-out-the-fashion-revolution- campaigns-for-consumers-awareness-of-working-conditions

- Thomas, A., Bilge, I.S. and Ballam, T. (n.d.). Greening and Indigenizing the Carpentry Trade. [online] pressbooks.bccampus.ca. Press Books. Available at: https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/cicancarpentryproject/front-matter/definitions/

Sustainably Speaking

Loughborough University Sustainability Blog