Why gender stereotypes in maths still matter and what they are doing to our students

In this blogpost, Serena Rossi, Iro Xenidou-Dervou and Krzysztof Cipora explore how belief in gender stereotypes around mathematics can influence male and female university students’ academic confidence, anxiety and performance differently. Using data from over 900 students, the research explains why some students may feel more anxious in maths than others, and how false beliefs about gender and ability can play an important role. Edited by Dr Joanne Eaves.

The full article describing this research can be found here https://nyaspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/nyas.14779 .

“I am just not a maths person”

This is a sentence many educators have heard, especially from young women. And indeed, some people would also say “Mathematics is for men but not for women”.

Even though men and women perform equally well in mathematics, the belief that men are naturally better at maths remains surprisingly widespread. This stereotype is not only outdated, but it can also harm students’ confidence and learning.

In our study, we found that University students’ beliefs about stereotypes like this one can significantly influence their confidence, anxiety, and even their actual performance in maths.

So, why should teachers, researchers, and students care? Because these false beliefs have real and unequal effects. In this post, I will explain how gender-based stereotypes in mathematics affect male and female students differently, why we must be careful with how we measure these effects, and what all this means for education.

The background: What we already know

We have long known that Maths Anxiety (MA) is a real phenomenon, defined as: “A feeling of tension and anxiety that interferes with the manipulation of numbers and the solving of mathematical problems in ordinary life and academic situations” (1). We also know that, despite performing similarly to men (2), women report higher levels of maths anxiety and lower confidence in their maths abilities (3). However, we are still learning why this gap exists.

One potential reason is the belief that maths is a “male domain” (men are better than women at maths) (4): a stereotype shaped by society, media, and culture. Our study examined how endorsing this stereotype affected students’ maths anxiety, their self-concept (how good they think they are at maths), and their arithmetic performance.

The study

We asked 923 university students to complete an online survey using a set of self-report questionnaires and a timed arithmetic task. We measured:

- Maths-gender stereotype endorsement, i.e. their level of endorsement of a series of stereotypes related to the idea that maths is for men but not for women.

- Maths anxiety, i.e. their level of anxiety related to both maths testing situations as well as everyday numerical tasks.

- Maths self-concept, i.e. how good students believe they are at maths.

- Arithmetic performance. their accuracy on a set of timed arithmetic tasks

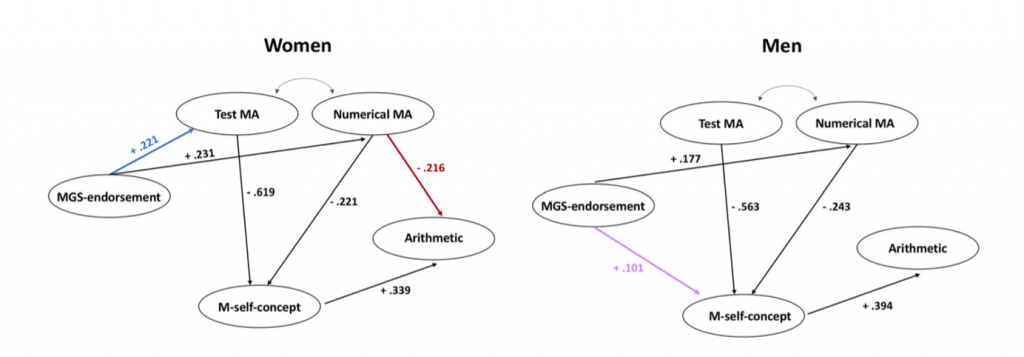

We then used Structural Equation Modelling (SEM), a statistical method that helps us to test how all these factors interact and influence each other, and whether this differed between men and women.

The findings, and why they matter

1) Stereotype endorsement affected women more negatively than men.

Among female students, endorsing the mathematics-gender stereotype was linked to higher maths anxiety, lower confidence, and poorer arithmetic performance. This was not a simple one-step process; rather, believing such stereotypes related to increased levels of anxiety, which in turn related to lower self-confidence, and finally reduced performance. In short, for women, endorsing negative stereotypes about their group can trigger a detrimental chain reaction.

2) Men were not unaffected, but the pattern was different.

In male students, the endorsement of these false stereotypes about women was associated with higher confidence in their maths ability. However, this boost came with a twist: endorsement of such stereotypes was also associated with higher numerical anxiety. This suggests that while gender stereotypes may increase men’s confidence, they may also place pressure on them to live up to those expectations.

3) The questions used in popular measurement tools may not mean the same thing for men and women.

Crucially, we found that men and women interpreted the survey questions differently (in technical terms: we did not obtain measurement invariance). That means that responses on self-report questionnaires about maths anxiety, confidence, and stereotypes cannot be directly compared across genders.

Figure 1 illustrates the results between women and men.

Discussion: What do we take away?

Our study shows that gender stereotypes in maths continue to shape how students feel and perform, even when men and women are equally capable. For women, believing the stereotype that “maths is for men” relates to them feeling increased maths anxiety, less confidence, and gradually pushes them away from maths. These beliefs are often learned over many years and can be one of the reasons for women’s lower participation in STEM fields.

In men, gender stereotypes relates to increased feelings of confidence in maths, although that leads to feeling pressured to live up to the expectations generated by these false stereotypes.

From a methodological perspective, future researchers should take into account the fact that women and men may understand and interpret questions about maths confidence, maths anxiety and gender stereotypes differently, meaning we need to be cautious when comparing their scores.

In short: Beliefs about gender stereotypes can shape students’ experiences of learning maths, and the gender differences we found may help explain why women remain underrepresented in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) fields.

Educational Impact: What this means for practice

- Challenge stereotypes early and openly: Educators and schools should talk openly with students about common gender stereotypes in maths and challenge them. Young people need to know that these ideas are false and damaging. These conversations should happen early, before negative beliefs take root.

- Support girls’ confidence in maths: Because belief in stereotyping is linked to higher maths anxiety and lower confidence in women, educators can play a key role in building girls’ maths self-concept. Praise effort, encourage risk-taking in problem solving, and give examples of women succeeding in maths-related careers.

- Use caution when interpreting surveys across genders: Many commonly used tools to measure maths anxiety and confidence may not be interpreted in the same way in men and women. Educators and researchers should be cautious about comparing scores between genders without first checking how different groups of students interpret the questions.

Reference list

1. Richardson, F. C., & Suinn, R. M. (1972). The Mathematics Anxiety Rating Scale: psychometric data. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 19, 551–554. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0033456

2. Devine, A., Fawcett, K., Szucs, D., & Dowker, A. (2012). Gender differences in mathematics anxiety and the relation to mathematics performance while controlling for test anxiety. Behavioral and Brain Functions, 8, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-9081-8-33

3. Hill, F., Mammarella, I. C., Devine, A., Caviola, S., Passolunghi, M. C., & Szucs, D. (2016). Maths anxiety in primary and secondary school students: Gender differences, developmental changes and anxiety specificity. Learning and Individual Differences, 48, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.02.006

4. Fennema, E., & Sherman, J. A. (1977). Sex-related differences in mathematics achievement, spatial visualization, and sociocultural factors. American Educational Research Journal, 14, 51–71.

5. Rossi, S., Xenidou-Dervou, I., Simsek, E., Artemenko, C., Daroczy, G., Nuerk, H.-C., & Cipora, K. (2022). Mathematics–gender stereotype endorsement influences mathematics anxiety, self-concept, and performance differently in men and women. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1513(1), 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.14779

About the Authors

Serena Rossi is a Lecturer in Mathematical Cognition at Loughborough University and part of the Centre for Mathematical Cognition. Her research explores how beliefs, emotions, and individual differences influence students’ learning experiences in mathematics. Krzysztof Cipora is an Associate Professor at Jagiellonian University in Krakow (Poland). Iro Xenidou-Dervou is a Reader in Mathematical Cognition at Loughborough University.

Centre for Mathematical Cognition

We write mostly about mathematics education, numerical cognition and general academic life. Our centre’s research is wide-ranging, so there is something for everyone: teachers, researchers and general interest. This blog is managed by Joanne Eaves and Chris Shore, researchers at the CMC, who edits and typesets all posts. Please email j.eaves@lboro.ac.uk if you have any feedback or if you would like information about being a guest contributor. We hope you enjoy our blog!