Colouring the SNARC Effect: Insights into Automatic Number Processing

This blogpost was written by Dr Krzysztof Cipora, a Senior Lecturer at the Centre for Mathematical Cognition. His research focuses on numerical cognition, exploring how humans process and understand numerical information across various contexts. Edited by Dr Bethany Woollacott.

In this blogpost, Krzysztof explores an intriguing aspect of numerical cognition: the automaticity of number processing. Krzysztof summarises his co-authored journal article on the well-known SNARC effect (Spatial-Numerical Association of Response Codes), linked at the end of the blogpost. This work shows that humans process numerical information even if they do not need to consider numbers’ meaning to solve the task at hand.

Introduction

We tend to associate numbers with positions in space, e.g., we tend to associate small numbers with the left and large numbers with the right. We can see this in our reaction times during cognitive experiments: when shown a number onscreen and told to press a button depending on the magnitude of a presented number, we press the button located on the left a bit faster when we respond to small numbers and the right-hand button faster when responding to the large numbers.

“…we tend to associate small numbers with the left and large numbers with the right…”

This phenomenon, known as the SNARC effect, has long intrigued cognitive psychologists. SNARC reveals how humans process numerical information and link it to space. What makes it even more intriguing is that the SNARC effect is present even when number magnitude is irrelevant to the task, e.g., when participants are judging whether the number is odd or even. But does this automaticity persist when tasks are based on judgements of non-semantic features, such as the colour of the font in which numbers are presented? This post discusses findings from two recent experiments that explore this question and their implications for understanding how we think about numbers.

Previous research

The SNARC effect was first identified in the 1990s and has been intensively investigated ever since1. Many research studies have observed the SNARC effect in studies where participants are asked to classify the magnitudes of presented numbers as smaller than or greater than a specific criterion value, like 5. However, as mentioned, the SNARC effect has also been observed in tasks where magnitude is not relevant, for instance, when participants are judging number parity. This observation raises questions on the automaticity of these number-space associations: participants do not have to consider magnitude when solving tasks about parity but there still appears to be an association between number magnitude and space. This suggests this association is automatic; however, when judging parity, participants still need to process the meaning of the number which perhaps requires them to consider magnitude.

Therefore, the automaticity of the SNARC effect would be much more convincing if it also appeared in non-semantic tasks where participants do not need to process the meaning of the number, for example, when asking participants to judge colours or the orientations of presented numbers. Evidence from such studies has been quite inconsistent so we designed two online experiments which aimed to investigate whether we could observe the SNARC effect in non-semantic tasks.

The tasks and our key findings

Experiment 1: Nominal Colour Judgement

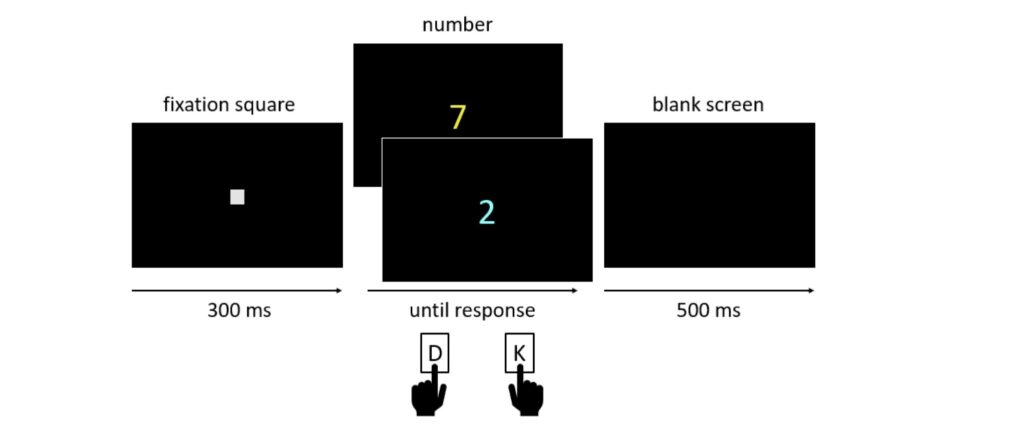

We asked participants to classify numbers based on their font colour (blue vs. yellow) – this task did not require the participant to consider any aspect of the meaning of the number (see below).

Despite the irrelevance of number magnitude, a small but significant SNARC effect emerged: faster left-handed responses were observed for smaller numbers and faster right-handed responses for larger numbers. This suggests that number magnitude is processed and associated with space even when magnitude is not relevant to the task.

“This suggests that number magnitude is processed and associated with space even when magnitude is not relevant to the task.“

Experiment 2: Colour Intensity Judgement

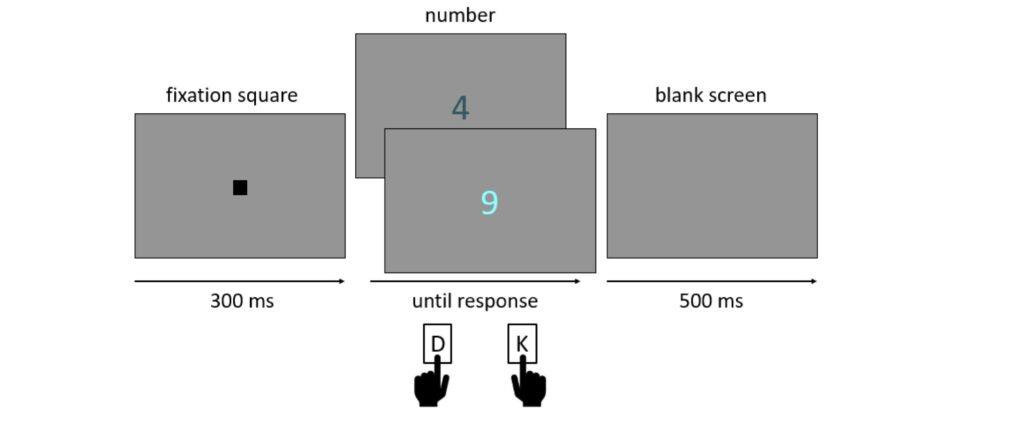

In the second experiment, instead of judging blue vs. yellow, participants judged whether the number was presented in light blue vs dark blue – see below. Again, the task did not require participants to consider number magnitude.

As before, the SNARC effect was observed, albeit with slightly reduced strength compared to the first experiment. This consistency underscores the automaticity of spatial-numerical associations.

Conclusion

These findings provide evidence of the automaticity of number processing in tasks involving non-semantic features like colour. This suggests that number magnitudes are automatically processed and associated with space.

Educational Implications

1. Insights into Numerical Cognition:

These findings enrich our understanding of how numerical information is processed, offering insights that may contribute to broader discussions on cognitive processing and automaticity in basic research contexts.

2. Relevance for Cognitive Models:

By demonstrating the robustness of the SNARC effect in non-semantic tasks, this research provides a foundation for refining existing cognitive models and theories about spatial-numerical associations.

3. Role of space in understanding numbers

In a broader sense, space seems to be a powerful tool for our minds to deal with numbers. However, we are still lacking an unified model on how these mechanisms work, and how they may be harnessed to support education. The research in this blogposts contributes to this fundamental research aiming to shed light on this issue.

Disclaimer: A ChatGPT model was used to support the writing of this blogpost. For more information, contact b.woollacott@lboro.ac.uk

Paper summarised in this blogpost:

Roth, L., Caffier, J. P., Reips, U.-D., Cipora, K., Braun, L., & Nuerk, H.-C. (2025). True colours SNARCing: Semantic number processing is highly automatic. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory & Cognition. Author accepted manuscript available at: https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/aeyn8

References

1. Dehaene, S., Bossini, S., & Giraux, P. (1993). The mental representation of parity and number magnitude. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 122(3), 371–396.

Centre for Mathematical Cognition

We write mostly about mathematics education, numerical cognition and general academic life. Our centre’s research is wide-ranging, so there is something for everyone: teachers, researchers and general interest. This blog is managed by Joanne Eaves and Chris Shore, researchers at the CMC, who edits and typesets all posts. Please email j.eaves@lboro.ac.uk if you have any feedback or if you would like information about being a guest contributor. We hope you enjoy our blog!