Non-binary 101

Author: David Wilson

“GLAAD’s Accelerating Acceptance 2017 survey reveals a remarkable new era of understanding and acceptance among young people who increasingly reject traditional labels like ‘gay/straight’ and ‘man/woman,’ and instead talk about themselves in words that are beyond the binary – they are, in essence, igniting an identity revolution.”

GLAAD

You’ve probably heard by now of people saying they’re non-binary or their gender is non-binary (sometimes shortened to “NB” or “enby”). Maybe you know someone who is non-binary. But what does it mean? Is it all just made up? This guide has been written to explain it clearly and simply.

What is a binary?

Binary means something can have one of two values. For example in a computer everything is defined by a series of “bits” and every bit has the value 0 or 1. Binary gender means seeing gender as only having two possibilities. We call these “male” and “female”. In most countries in the world every baby born is assigned one of these two values based on their genitals.

What is gender?

To understand any category of gender we must understand what gender is. A person’s gender is a way of categorising them – normally using measures of masculinity and femininity. Everyone has their own balance of traits which we think of as masculine or feminine. Some people may be very masculine and not very feminine, or very feminine and not at all masculine. Most people are a mix of both.

Someone’s gender identity is their own experience of their measures of the masculine and feminine. Their gender expression is how they display that outwardly through their behaviour and appearance. The two might be quite different, depending on how free a person feels to “be themselves”.

For more on this balance of masculinity and femininity, and the difference between identity and expression see The Gender Unicorn from http://www.transstudent.org

Many trans people experience gender dysphoria which is the feeling that their gender identity doesn’t match the body they have, or the way they’re expected to present and act based on their body. Its intensity can vary but it can have a serious impact on people’s ability to live their lives.

What is a social construct?

You may have heard people say “Gender is a social construct.” This means it’s something that we create within our societies, a bit like laws, language or social norms like greetings and traditions.

Social constructs vary by location

Because they are made up, gender norms such as hair length and clothing styles vary in different societies and cultures, just like laws and traditions do. Think about how different traditional male presentation is in cultures such as native America, Scotland, Austria and Arab or Asian countries to give just a few examples. This is how we know it is something we’ve invented as opposed to being something fixed like the laws of physics which are the same everywhere and existed before humans.

Social constructs also vary over time

Our image of gender has also changed hugely over time. Consider this image of Alexander The Great, painted circa 1494 to depict Alexander as the epitome of strength and power having conquered the entire known world. It is reasonable to assume that both Alexander and the artist, known as Master of the Griselda Legend, considered Alexander to be extremely masculine, an example of the ideal man for other men to aspire to. If we deconstruct his appearance as depicted and compare it to our 21st century Western norms however, things look quite different.

His hair is long – something we associate with women and femininity. His one-piece garment, covering his torso and upper legs would be called a tunic then, but now we call them dresses and say they are only for women. His skin-tight leggings (feminine) are pink (feminine) and his gold ankle boots (feminine) would certainly attract comment on a man now.

His body is slim, without the rippling muscles we see in modern examples of masculinity on magazine covers and action film posters. But perhaps most remarkable is his pose. The coquettish tilt of the head, and the flexed hand against his out-thrust hip. It would be hard to find a pose that more accurately depicts the camp femininity often associated, wrongly, with gay men.

Why have we constructed gender the way we have?

Social constructs often define power relationships. For example apartheid in South Africa empowered white people and disempowered black people. With gender the power has been controlled by a system known as patriarchy which empowers men and glorifies masculinity while disempowering women and demeaning femininity. Polarising gender into a binary maintains this.

Gender and biological sex

We often confuse gender and sex because we use the same words, “male” and “female”, for each. We’ve described gender as your own experience of your combination of masculinity and femininity. Your sex is a description of your biology, i.e. your body.

Even people who understand that gender can be broader than male or female, often see sex as more of a strict binary: “You’re either a boy or a girl when you’re born”. We all learn about reproduction and genetics at school so most people think they understand this science. But this view is incredibly simplified at the level to which most people study it. In reality it is more complicated. Sex is really a combination of 5 things:

External genitalia (e.g. penis, vulva)

Internal genitalia, or gonads (e.g. testicles, ovaries)

Levels of various hormones (e.g. testosterone, oestrogen)

Genetics (XX, or XY, though as noted above that distinction is not black and white)

Secondary characteristics (amount of breast tissue, facial hair, Adam’s apple etc.)

Some people’s genitals at birth are not clearly male or female. Medical professionals in most countries classify these people as intersex but with the parents will decide whether the child should be raised male or female (and may carry out surgery on the baby to make the genitals more “normal” for that sex).

It is more common than most people realise to have different combinations of these five characteristics. For instance, some people raised as male are found to have ovaries when they have surgery or a scan. If they never had this the ovaries would never have been noticed. Most people never have their hormone levels tested, so can’t be sure whether the balance is what they would expect for their sex. Genetics is also more nuanced than most people realise, and many people cannot be clearly categorised as XX or XY. They are somewhere in between.

When we meet people and guess their sex, we really only have secondary characteristics to go on – ignoring the fact we have no information at all for the other 4 primary aspects of their sex.

Science now clearly backs up the view that sex is complicated, and not a clear binary. See the ‘Sex redefined‘ article in Nature journal.

If sex isn’t binary, and gender is a social construct based on sex, then gender can’t be binary. It would be a bit like a tree with more trunks that branches.

Some trans people change aspects of their physical sex through surgery and/or taking hormones in order to better match their gender identity. The medical profession is now starting to get better at helping people do this for non-binary identities.

Models of gender

So gender norms vary by location and time (even within lifetimes), but for a given location at a given time people often have extremely rigid ideas of what makes for an acceptable male and an acceptable female. For instance we typically think a man should be tall and strong with short hair, and women should be small and dainty with long hair. Of course we all know people who don’t fit these expectations.

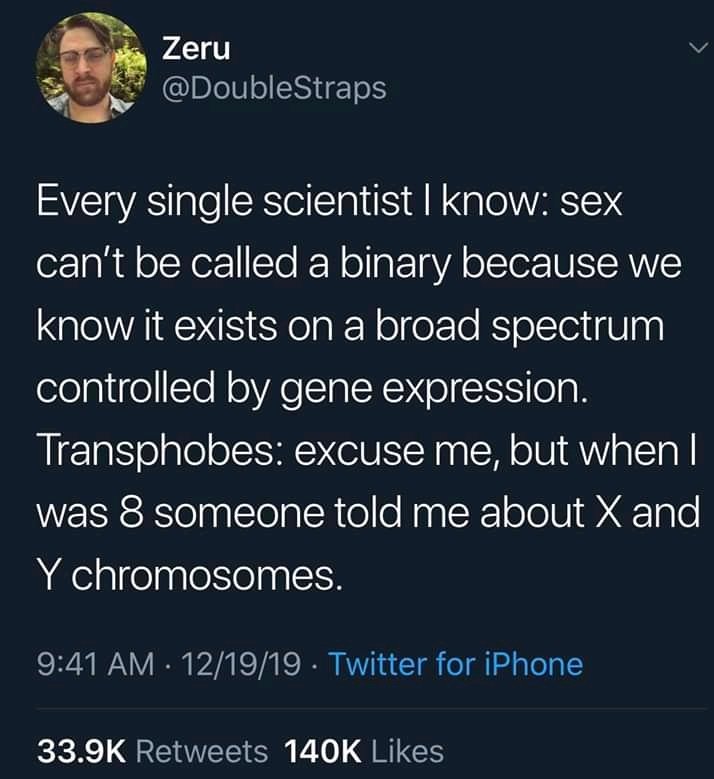

Because people think there are only two options for gender society tries very hard to categorise everyone into one of the two. Then we criticise many people for not being a good enough fit. This is obviously terrible for the self-esteem of people who are deemed “not like they’re supposed to be”, especially if they themselves also believe there are only two genders.

When these people learn the truth about gender the sense of freedom can be enormous.

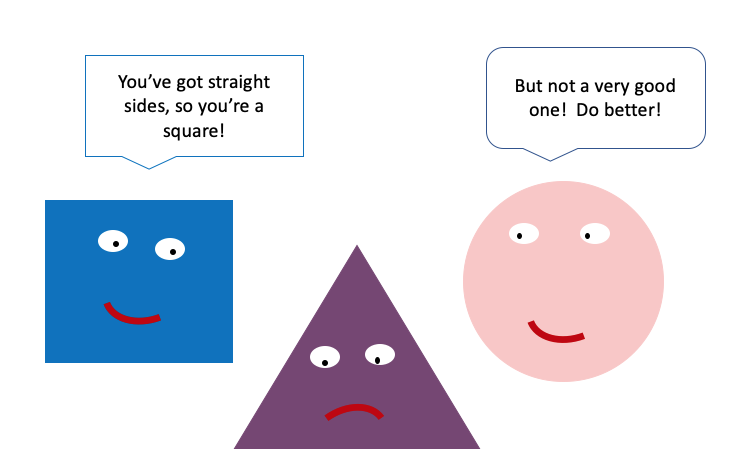

Some trans people who are raised as male realise they fit better in the category of female, or vice versa. Indeed this is really the only option a lot of people have been given when they say they don’t fit the gender they’re expected to. But not being an apple doesn’t necessarily make you an orange.

Realising you can reject your assigned gender without having to try and fit the standards of another can be incredibly liberating, but sometimes scary too.

Imagine everyone thought you were a duckling. But you didn’t look like ducklings are meant to look, so they said you were “ugly”.

…see where I’m going? You knew this all along!

Gender and sexuality

A lot of people think they can tell who is gay or lesbian by how they look or act. If they see someone they categorise as male but effeminate they often decide they’re gay. Or similarly if they decide they’re a masculine woman. People even predict a child will be gay based on the toys they like or clothes they dress up in. But attraction isn’t about who you are or what you’re like, it’s about who you are sexually and/or romantically drawn to. You can’t tell who someone is attracted to by looking at them (okay maybe if you watch them so much you see all of their sexual encounters, but that’s not okay!). What people are really observing is not the person’s sexuality but their gender expression.

One of the reasons people get mixed up about gender and sexuality is the way we categorise sexuality. The labels depend on who you want to have sex with AND what your own gender is. If two people like pasta, we’re fine with that and it doesn’t matter what sex or gender they are. It doesn’t even matter if they’re Italian! But if two people are sexually attracted to women we categorise their sexuality based on whether they are also women. If they are women most people will say they’re “gay” or “lesbian”, if they’re men they’re “straight” or “heterosexual”. (Of course we know either of them could be bisexual!)

We describe heterosexual as being attracted to the “opposite” sex. But that only works if sex is binary and we’ve already established it isn’t.

“The opposite of a human man isn’t a human woman. It’s probably some sort of trans-dimensional octopoid slime beast.”

Andrew O’Neill Pharmacist Baffler

If gender isn’t binary then the system for categorising sexuality starts to fail us. If gender is so complex that everyone’s gender is a unique combination of masculinity and femininity then concepts like “homosexual” (attracted to only the same gender) and “heterosexual” (attracted to only the opposite gender) become much less meaningful.

It’s also not really clear whether by “same” and “opposite” we’re talking about gender or sex (you’ll notice this section has used a mixture of the two). Traditionally we tend to talk about “same sex” and “opposite sex”, but we’re clearly not attracted to people based on their genitals, gonads etc. so it probably has more to do with gender. But then we’re not attracted to everyone who shares the same gender identity (i.e. all men, or all women). It depends much more on hundreds of individual features and personality traits. So why do we pretend that sexuality is all based around one category at all?

Gendered toilets, facilities and events

Everyone knows you can only talk about trans issues for so long before you talk about toilets! A lot of toilets present a real problem for non-binary people because they are labelled using binary gender. If you’re neither male nor female, which should you pick? It’s like asking all people in the world to choose whether they’re “black or white”, “Muslim or Christian”, “tall or short”. Using either gendered toilet risks being accused of being in the wrong place and could lead to embarrassment or even violence. Even people who identify as male or female but don’t “fit the mould” face this problem.

Why do we have gendered toilets?

“We’ve all grown up with gendered toilets, so we understand that they’re necessary to keep people safe and decent. If you allowed men and women to use the same toilets they would have sex there, maybe without consent. In keeping men and women apart we ensure this doesn’t happen. It’s the same reason we have separate schools, women aren’t allowed into gentlemen’s clubs or golf courses and no woman must ever be in the same room as man she is not related to without a chaperone”. [/satire]

Clearly these ideas only hold up if everyone is heterosexual (which they are not) and don’t have self-control (which they do). They come from an era of Victorian sex-negativity and shaming. We have shaken off these attitudes in many areas, but they seem to persist with toilets. Even single-user toilets are often gendered as if people of different genders can’t use the same facilities…

…unless you’re disabled of course. Or at a festival, or on a plane, or a train, or a small café with one loo. You probably also have a gender-neutral toilet at home.

Gendered toilets also create problems for architects and building users because someone has to guess how many men and women will be using the building. Look how often women have to queue for toilets in theatres etc. when men don’t. If there were just lots of toilets anyone could use it would be fair for everyone.

It’s not just toilets

Lots of other facilities are gendered. For instance changing rooms in gyms and swimming pools, or clothes shops. Anyone not matching the expected model of “male” or “female” can and do get turned away from both, whether they are non-binary, trans or cisgender (meaning their gender identity matches the sex they were assigned at birth).

Then there are events – if the Race For Life is only for women, can non-binary people take part? Stag and hen nights are for groups of men and women – which should you go to if you’re non-binary? What about sports? Do you compete in the men’s tennis or the women’s?

Thankfully more and more buildings are adopting gender-neutral toilets, and some sports are moving in the right direction. Roller Derby allows non-binary people to compete in either the men’s or women’s game and the 2020 Olympics will have some mixed gender events. But there is a long way to go.

Pronouns

Gender is hard-coded into most languages. We use gendered words called pronouns when we talk about people, e.g. “he, him, his” for men and “she, her, hers” for women. We normally guess which to use based on someone’s name and appearance.

In English we also have a set of pronouns which don’t depend on gender. A lot of non-binary people prefer to be referred to using these pronouns.

| They | Them | Their | They are nice I like them That is their house |

“But ‘they’ is plural! It is only used for multiple people!” a person will often shriek when asked to use “they” for a non-binary person. But as it turns out they are wrong. They probably use “they” to talk about one person all the time. I’ve just done it, and you might not have even noticed. When we don’t know the gender of a person we’re talking about we use “they” naturally. For example imagine you’re in a meeting and somebody interrupts to tell you there is someone at reception who wants to speak to you. You might ask

“Do you know who they are?” “Could you ask them if it’s urgent?” “Did they give you their name?”

People have also created new pronouns which are not gendered which some non-binary people use, for example:

| Ze | Zir | Zirs | Ze are nice I like zir That is zirs house |

It can be difficult to get used to non-gendered pronouns. Even non-binary people who use them sometimes make mistakes. It takes some effort to change your mental programming. But it is important to use the pronouns a person wants used when talking about them (there I go again). If you’re not sure what pronouns they use, just ask. If you make a mistake, it’s not a big deal. Just correct yourself and move on.

Are non-binary people transgender?

Transgender is normally defined as someone whose gender identity doesn’t match the sex they were assigned at birth. So, if you were assigned male or female at birth but your identity is non-binary then it is valid to say you’re transgender. Not all non-binary people use this label though, and it is up to individuals to decide if they want to.

What about genderqueer, genderfluid, agender etc?

Non-binary is often seen as an umbrella term for all of the more specific gender identities which fall outside “man or woman”, as well as being an identity in itself.

That’s all folks!

Some people, whether they’re cis or trans, are very happy to identify as male or female, and that’s fine. But you don’t have to be one or the other!

Now your head is full of thoughts of gender, why not fill in your own Gender Unicorn? Have you ever thought about where you lie along each of these lines?!

Article photo by Marc Sendra Martorell on Unsplash

Equity, Diversity and Inclusion

Reflections, comments, discussion and opinion on EDI topics from Loughborough University staff and students

Join the discussion

1 Comment

Maia celebrates: International Non-Binary People’s Day – Equality, Diversity and Inclusion

[…] what identifying as non-binary means, Loughborough colleague, David Wilson has previously written a fantastic blog post that covers […]