Weekly digest – 17.06.20

The contentious nature of statues and monuments is nothing new, and neither is their downfall, as witnessed in Bristol with the statue of Edward Colston last week. A famous early toppling was in 1871 with the bringing down of the statue of Napoleon Bonaparte in the Place Vendôme, which like the falling of the Colston statue had a certain performative aspect and the images of Napoleon became artistic objects in their own right. The toppling of a statue is such a symbolic act that it is now something of a pre-requisite when it comes to regime change, whether that be the end of Lenin, Nazi Germany, Saddam Hussain or the break-up of the former Yugoslavia. Statues and monuments are invested with so much capital and so much meaning that history can, and often does, re-assess whether they deserve to be given a place within our public sphere. They have become a fascinating subject for art historians, anthropologists and artists. Even Loughborough’s Sockman faced a wave of protest when it was first installed in 1997.

The issue of statues to individuals who were implicated in slavery is something that has been prevalent in the US for some time. In August 2017, violent clashes broke out in Charlottesville, Virginia, when extreme right-wing groups contested the city’s decision to remove a statue of Southern Confederate Commander Robert E Lee. The events started a major debate on the future of American Confederate monuments and there has been continuing tensions over these memorials to slavery. Some contemporary artists have been commissioned to create statues and artworks that provide alternative representations of slavery and race. In 1993 in Birmingham, Alabama, a series of sculptures were erected to commemorate the civil-rights movement. One of the most impactful was by the artist James Drake that was located in a park where you had to walk through a passageway of snarling dogs. Rebecca Solnit in her article The Monument Wars described it thus; ‘the sculpture suggests that to understand the violence people once met here, we need to experience at least a shadow of that violence ourselves. It’s a rare thing, an official memorial to institutional savagery on the site where it transpired’. The artist Theaster Gates has created work in response to this history of racist statues within his Dancing Minstrel sculptures and in works such as Shoe Shine Stands which he constructs and uses oversized representations of shoe shining stands as symbols of power and acquiescence. Before the toppling of the Colston statue the artist Hew Locke had turned his attention to the statue, and others, in a project called Restoration where he re-considered their role and status and gave them a ‘statue dressing’ subverting them and imbuing them with new meaning.

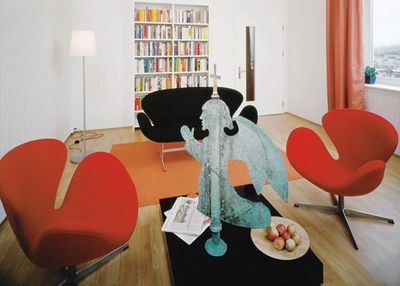

This interest in statues and how an artist might subvert or re-purpose them is something that is central to the work of Japanese artist Tatzu Nishi. I first came across his work at the Liverpool Biennial in 2002 where he built a functioning hotel room around the city’s statue of Queen Victoria. Villa Victoria operated as a hotel for the duration of Biennial with the statue in the middle of it. The statue, like many Victorian statues was on a high plinth but by constructing this room around its base visitors could have a direct engagement with the statue at the same floor level.

Tatzu has continued to build structures around statues across the world since with a range of memorable project such as Hotel Ghent. With such ambitious projects there is always a strong risk of failure and unfortunately one of these happened when we invited Tatzu to develop a work for the LU Arts and the Cultural Olympiad in 2012. After researching Loughborough’s history, he found that Thomas Cook’s first paid travel trip was from Leicester to Loughborough. There is a statue of Thomas Cook outside Leicester train station and his proposal was to recreate that first journey by Thomas Cook by removing the statue and taking it on the train to Loughborough and then to the locations that were part of that first journey. The train company and Leicester City Council both agreed to it and we were well advanced in our planning when at the 11th hour the City Council got cold feet, worrying about negative publicity, and pulled the plug on it. It is a shame as I think it would have been a memorable project!

Nick Slater

Director, LU Arts

The Limit

The Limit showcases the creativity that exists within the student population, creating a sense of community.