Intersectional Environmentalism: Why it’s crucial for climate justice

“[Equality] can be and should be achieved to ensure a life of dignity for all. Political, economic and social policies need to be universal and pay particular attention to the needs of disadvantaged and marginalised communities“

UN Sustainable Development Goal 10: Reduced Inequalities

In 2009, at the UN Copenhagen Climate Summit, a document called “The Danish Text” was leaked. It contained an agreement made between only a few rich developed nations, called “the inner-circle”, which included the UK and the US. The agreement set out to abandon the Kyoto protocol, the only legally binding treaty which held these richest countries accountable for their historic emissions and therefore have to commit to significant reduction targets.

Instead, “The Danish Text” was to set an agreed target to cap global temperature rise at 2 degrees Celsius. At the time, this was more than double the amount of warming experienced so far. Not only this, the agreement stated poorer countries could not emit more than 1.44 tonnes of carbon per person by 2050, whilst giving richer countries an allowance of 2.67 tonnes. The agreement also flipped the responsibility of climate adaptation and mitigation onto poorer countries by stating any funds or resources they needed was now dependent on them taking “a range of actions”.

This secretly agreed 2 degree cap and generous 2.67 tonne per person allowance would give countries like the US and UK a comfort blanket of continued economic freedom and development whilst snatching the covers off developing countries. It would lead to even more frequent storms, floods, and droughts for nations like Haiti and Bangladesh, and therefore threatening conflict, poverty, famine, and displacement.

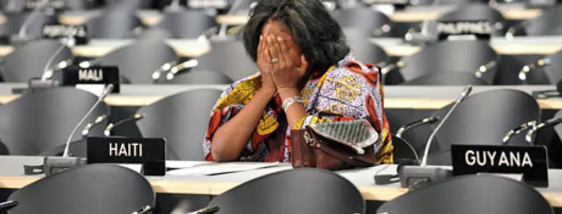

News of the leak was met with outcries filling the conference centre from countries like Africa shouting “2 degrees is suicide”. Mithika Mwenda of the Pan African Climate Justice Alliance described the conference as “a matter of life and death for the friends and families of those that are here”, and going home with a 2 degree agreement would be “signing a death warrant” for nations like Haiti and Bangladesh.

Tensions came to a head when after continuously banging her fist against the table in frustration at feeling ignored, lead Venezeulan negotiator Claudia Salerno accidentally cut her hand. In an act of desperation, she thrusted her bloody palm in the direction of UN officials and the Danish hosts remarking: ‘”Do you think a sovereign country has to actually cut its hand and draw blood [to speak]?”

Salerno’s bloody palm came to represent the intersection of racial inequality and climate change. The notion that richer developed nations were willing to sacrifice the lives of millions of ethnic minorities to extend their “business as usual” exposed, in the words of Naomi Klein writing for The Nation, “the reality of an economic order built on white supremacy [as] the whispered subtext of our entire response to the climate crisis, and it badly needs to be dragged into the light.”

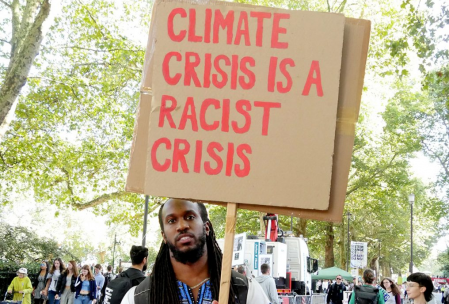

Though the events of COP-09 are now a faded memory for most, the recent resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement made the event resurface in my mind as a clear symbol of how climate change is not just an environmental issue.

Intersectional environmentalism is the understanding that the injustices happening to the earth also have an overlapping social aspect. That social issues such as racial or ethnic marginalisation, gendered discrimination, urban/rural divides, and poverty all shape or are shaped by environmental injustice. That when we think about vulnerability to climate change, this cannot be viewed through a single geographical lens, but instead should be seen as a multi-dimensional process. We must bring critical social issues of equity, access, distribution, and causation vs. exposure to the forefront of our understanding. Therefore, when we push for climate justice, we must also push for social justice.

One recent example which highlights the necessity for an intersectional understanding of environmental issues is the race gap in air pollution. In a study conducted by the University of Minnesota, researchers found that pollution in America is ‘disproportionately caused by whites, but disproportionately inhaled by Black and Hispanic minorities’. The study concluded that whilst Blacks and Hispanics were exposed to over 50% more pollution than they caused, non-Hispanic whites experience 17% less than they cause.

Co-author Jason Hill describes the white experience as “pollution advantage” – longstanding societal inequality in terms of wealth and access means whites consume more and consequently pollute more yet ethnic minorities are more likely to live in locations with higher concentrations of pollution – “pollution burden”.

This example of the intersection of race and climate is not just visible in the US. When Public Health England reported that BAME Britons were up to twice as likely as white Britons to die if they contracted coronavirus, they pointed to historical and systemic racism as potential root causes for this uneven risk. However, their reports have been heavily criticised by scientists over their omission of the unequal burden of air pollution. Rosamund Kissi-Debrah, a World Health Organisation advocate for health and air quality, remarked “air pollution is linked to diabetes, strokes, heart attacks, asthma attacks, and those with underlying health conditions are dying more from Covid-19.”

In the words of Lise Kingo, The United Nation’s sustainable business chief, there are “very, very clear connections” between COVID-19, the climate crisis, and the Black Lives matter movement – with the three intersecting to reveal “deep-seated and structural inequalities”.

Earlier this year, Loughborough University signed the United Nations Sustainable Development Accord. In February’s edition of the Sustainability Newsletter, I explained a bit more about what the goals of the accord were, and what it would take to achieve them. I wrote:

“The SDGs recognise the interdependence of social, economic and environmental challenges; that ending poverty and hunger goes hand in hand with improving health and education, reducing inequalities, fostering peace, spurring economic growth, preserving our planets resources and tackling climate change. Furthermore, these goals can only be achieved through global solidarity and the participation of all countries, stakeholders, and people.”

The goals exist to recognise the intersectionality of environmental, social, political, and economic issues. Therefore, they highlight the need for countries, governments, organisations, and institutions to address social injustice and climate injustice as interlinked problems with interlinked solutions. And that these solutions must be supported through equity of responsibility, and not “business as usual” for developed nations.

Therefore, real climate justice is to connect the dots between climate and social injustices and tackle these together to build resilient and equitable communities, whilst paying “particular attention to the needs of disadvantaged and marginalised communities”. Why? As they are the most exposed to the numerous geographical and social burdens of climate change – whether this is temperature rise in Haiti, flooding in Bangladesh, or asthma in the UK – that richer developed nations have historically caused.

Sustainably Speaking

Loughborough University Sustainability Blog