Citizen scientists have a crucial role to play in flooding research

Avinoam Baruch on how there comes a point when we all need a little help from our friends – and for researchers this is no different. Step forward the citizen scientist.

Public or amateur participation in research is not a new thing, but the growth of digital technology has provided researchers like me with new ways of engaging with the wider public.

Citizens: the driving force of research?

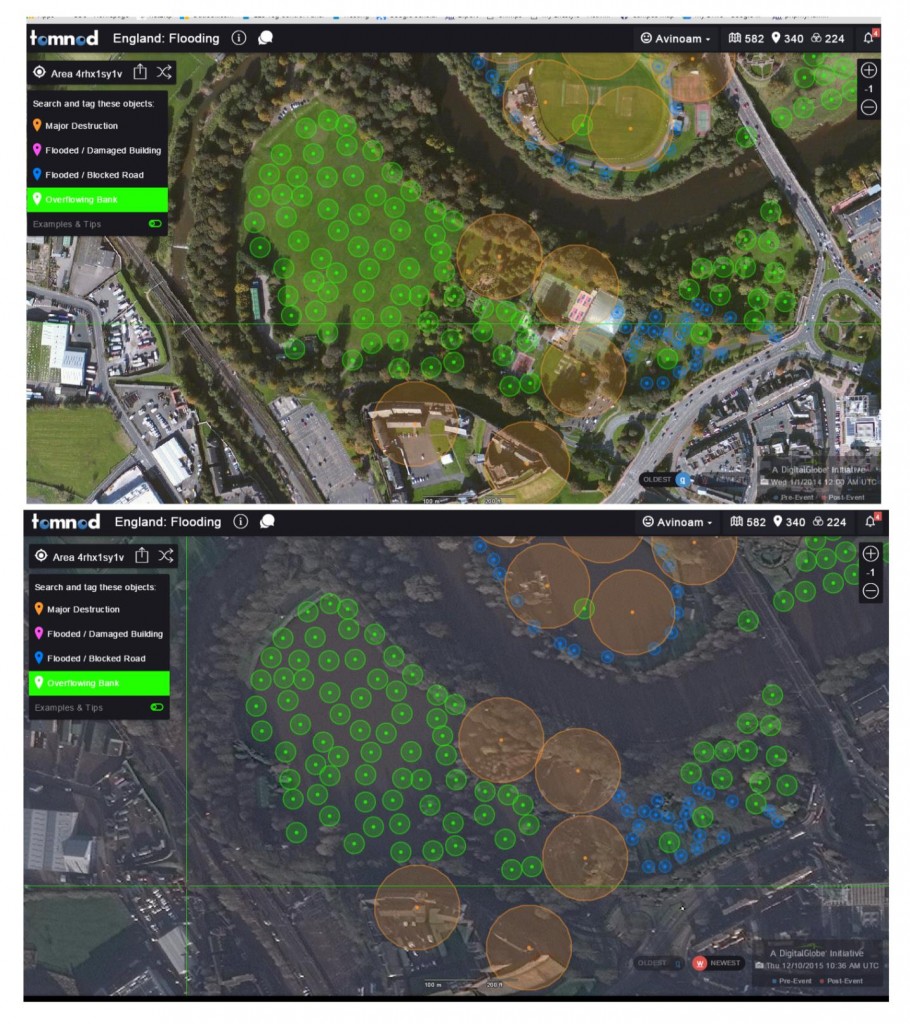

Crowdsourcing is particularly useful when it comes to enlisting helpers to measure the devastation caused by flooding. Under the supervision of Dr Dapeng Yu, Senior Lecturer in Geography, and Dr Andrew May, Research Fellow at Loughborough Design School, I was able to map and identify Storm Desmond’s flooding destruction in Carlisle and the surrounding areas, after more than 700 members of the public successfully tagged satellite imagery. Between 2,200 and 3,500 homes flooded in Carlisle after key flood defences failed.

The quality of the tags was high, particularly in rural areas. And where citizen scientists found it difficult to identify flooded areas, we surveyed the depths of the floods on the ground by examining marks on walls of public buildings.

This local knowledge has proved invaluable in helping to improve our understanding of the magnitude and management of flooding in the UK, and was made possible thanks to Tomnod – a Colorado-based satellite crowdsourcing project.

Tomnod, run by commercial satellite company DigitalGlobe, makes public its online map interfaces in order to encourage as many people as possible to each view and tag a small section, which in this instance, is for signs of flood damage.

Tomnod, run by commercial satellite company DigitalGlobe, makes public its online map interfaces in order to encourage as many people as possible to each view and tag a small section, which in this instance, is for signs of flood damage.

This new method of knowledge sharing has also been used in the hunt for evidence of the missing Malaysian Airlines flight MH370.

In short, there is nothing else quite like this which puts high quality satellite imagery to good use – and its potential is huge.

The next steps will be to produce a detailed map of the flooding devastation, assess data quality, run flood simulations and evaluate the role that such data can play in flood risk management.

Although the Tomnod Storm Desmond campaign has now finished, anyone can still help with this research by sharing their photos and observations of the floods through a new campaign called Floodcrowd. This has been set up as part of my PhD to crowdsource information which can help in flood risk management.

This initiative is linked to two recent Research Councils UK (RCUK) projects on climate services, funded by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC), including Mapping Flood Risks with Future Flow and Precipitation, led by Dr Yu, and Drone Watch led by Cranfield University in which Dr Yu is a Co-Investigator. In both projects, particular emphasis is placed on the role of satellite, drone and aerial photography for flood analysis. Feel free to email me for more information.

Technology can make scientists of us all

As geographic research studies continue to grow more ambitious, the need for localised up-to-date information becomes integral to managing environments. Through Tomnod it is possible for members of the public or ‘citizen scientists’ to contribute high quality data and play an integral part in helping to inform a wide range of scientific research. Their input is invaluable.

The sharing of data in this way helps scientists build stronger relationships with the communities they aim to help. My research focuses on investigating public motivations for participating in crowdsourcing projects and the use of crowdsourced data for modelling flood risk hazards and vulnerability.

So there you have it; crowdsourcing is an effective way of collecting a lot of data in a short period of time, and new technology is enabling amateur scientists to gain the skills needed to contribute to important research. Isn’t it about time we embraced the rise of the citizen scientist?