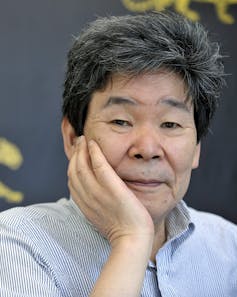

Remembering Isao Takahata, the Japanese animator who made us see the world as children

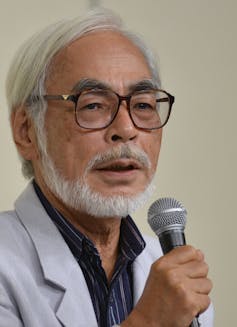

The recent death of Studio Ghibli’s co-founder, producer and director Isao Takahata has prompted a proper recognition of his work, liberating it from the shadow of his more celebrated partner, the Pixar-championed Hayao Miyazaki who unlike Takahata, also designed and animated.

But for animation scholars, critics and fans, Takahata’s films always had the same resonance, and foregrounded their own style and preoccupations. Takahata, unsung in many respects, defines the Ghibli style as much as Miyazaki; his grasp of the beauty of the mundane and his impressionistic apprehension of memory and feeling, is as memorable as Miyazaki’s epiphanies in flight.

Toei story

Both began their careers at the Toei Studio, Takahata directing the commercially unsuccessful Horusu, Prince of the Sun or The Little Norse Prince (1968), on which Miyazaki served as an animator. The pair then achieved success on the Takahata-directed and Miyazaki-designed Panda Kopanda films (1972/1973), as well as TV work, and the literary adaptations produced by Nippon Animation, including Heidi, A Girl of the Alps (1974).

Takahata directed features Chie the Brat (1981) and Gõshu the Cellist (1982), before joining Miyazaki to produce Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), along with long-time collaborators, composer Joe Hisaishi and producer Suzuki Toshio, with whom they went on to form Studio Ghibli.

The studio’s manifesto was to focus on the artist auteur and produce high quality animation, a significant risk in the highly commercial Japanese market of the time. Within three years, Studio Ghibli had produced what have become two acknowledged masterpieces, Miyazaki’s My Neighbour Totoro (1988) and Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies (1988), the latter the product of Takahata’s personal convictions as an anti-war activist.

An adaptation of a short story by Akiyuki Nosaka, the film is informed by Takahata’s own wartime memories in Okayama as he tells the tale of an orphaned brother and sister, Seita and Setsuko, as they try to survive after the allied fire-bombing of Kõbe, Japan, in World War II.

Again, for those invested in animation as a form, it comes as no surprise that an animated film can deliver narratives of significant import and emotional affect. Though like Miyazaki, Takahata’s films feature children and childhood, and depict the childlike in such sensitive ways, they are never childish nor made only for a children’s audience. Rather they speak to the commonality of experience for adults and children, and use the emphases on everyday gesture that animation so powerfully amplifies – the cutting of fruit, a baby pursuing frogs, picking a flower, placing a comforting hand on a shoulder – to communicate universal themes and connections.

Japanese legend

I had the good fortune to meet Takahata at Ghibli, and, though he did not draw himself, he noted that drawing always suggests the hand that creates the image, and as such, the human feeling that resides within it, and might be shared. He argued, too, that drawing always reminded him of the resourcefulness, energy and vulnerability of the child, which he tried to show in his films.

Inspired initially by his studies of French literature in the 1950s, and particularly the poetry of Jacques Prévert, Takahata was enthused by an animated adaptation of Prévert’s Le Roi et l’Oiseau (1952) – The King and the Mockingbird – made by director Paul Grimault. Grimault’s lyrical style and colour palette were influential on Takahata’s more realistic cartoon aesthetic, but as his oeuvre developed, a sometimes more comic-strip approach, such as in My Neighbours the Yamadas (1999), or a calligraphic style, like The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013), emerged in telling a particular story.

This calibration of form and subject enabled Takahata to adopt different tones and outlooks on what were essentially potentially tragic themes – suffering and death in Fireflies; pastoral utopia and urban drudgery in Only Yesterday (1991); environmental transformation in Pom Poko (1994); and dysfunctional families in the Yamadas.

Crucially, Takahata drew upon the distinctive language of expression available in animation, often using metamorphoses and visual metaphors to move seamlessly between comic vignettes and serious observations, often prompting heart-wrenching, bittersweet endings.

Takahata observed that he didn’t believe audiences watched live action films carefully, but that animation forced them to do so, because it produced reality more solidly than it actually is. This is surely never more affecting than in Setsuko’s demise in Fireflies and the poignancy of her question, “Why do fireflies have to die so soon?”

Takahata once perceived himself to be a failure because he had not made a film like Frederic Back’s The Man Who Planted Trees (1986), with its vivid commitment to human endeavour and the power of nature. But his own legacy refutes this self doubt, offering stories of human aspiration, good humour, love and the belief in life, in the face of the world’s challenges.

Takahata’s masterpiece, Grave of The Fireflies, the story of two children surviving after the end of WWII. Studio Ghibli

![]() As we wipe away our tears when watching Fireflies, we might hear the voice of Takahata himself, in the guise of a smiling man, who speaks to the children and says, “Beautiful day, in spite of it all …”

As we wipe away our tears when watching Fireflies, we might hear the voice of Takahata himself, in the guise of a smiling man, who speaks to the children and says, “Beautiful day, in spite of it all …”

Paul Wells, Director of the Animation Academy, Loughborough University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.