Power, journalists and sleaze

The Man in the White Suit

In 1997 Martin Bell, BBC war reporter, became ‘the man in the white suit’. At the behest of Alistair Campbell Bell stood as an independent candidate in Tatton, one of the safest Conservative seats in the country, and trounced Neil Hamilton, who was embroiled in the so-called ‘cash for questions’ scandal. Hamilton had been accused by The Guardian newspaper of taking cash, amongst other things, from Mohamed Al-Fayed, the owner of Harrods, in return for asking questions in the House of Commons. Despite dropping his libel case against The Guardian Hamilton was not deselected by the Tatton Conservative Party and this prompted Bell to don his white suit, symbolising his ‘anti-sleaze’ stance. At the time there was a broadly-shared public sentiment that Hamilton was not a ‘bad apple’ but indicative of widespread corruption in the Conservative Party that had been in power for too long, had run out of ideas, and had their fingers in the till. As BBC political correspondent Nick Assinder wrote in a retrospective analysis the Major government: ‘If there was one word that came to epitomise the last Tory government it was “sleaze”’

Almost two decades on from ‘the man in the white suit’, what is remarkable looking back is that sleaze was seen predominantly as an issue attached to one particular party rather than as a more general phenomenon affecting all parties. This is part and parcel of a growing distrust of the political elite since the 1990s, whichever party they represent, based on the notion that politicians are in it for what they can get out of it rather than for some lofty ideal of public service and that fundamentally they are ‘all the same’. Such distrust helps to explain the rise of challenger parties such as UKIP and the Greens. So what happened to transform ‘sleaze’ from simply a vote-loser for the Conservative Party in 1997 to an issue haunting all parties in the current General Election?

‘Tony’s Cronies’

Tony Blair came to power in 1997 promising to be ‘purer than pure’ but New Labour were famously ‘intensely relaxed’ about people becoming ‘filthy rich’. As the Blair-Brown years unfolded more and more people came to see this attitude not only as an acceptance of macro ‘trickle-down’ economics but also at a meso- and even micro-level, as a means of raising money from rich donors initially for party funds and then for private gain. The idea that rich people could affect government policy or could acquire a peerage by donating to the Party became well-established by drips. The Bernie Ecclestone affair was merely the first of a number of New Labour sleaze scandals in 1998 when connections were made by some between Ecclestone’s £1 million donation to the Labour Party and the decision to exempt Formula 1 from the ban on tobacco advertising. Reflecting on his premiership in 2007 Tony Blair said that he had regretted attacking the Major government so much for sleaze because it gave the false impression that all politicians are the same: “”The bad apples are actually few and far between and it really doesn’t help public life at all in the end when we end up trying to make it look as if our politics is sort of corrupt when it isn’t.”

Flipping the Election

In the run-up to the 2010 General Election the C4 Dispatches programme caught three formerly high-ranking Labour ministers, MPs Stephen Byers, Patricia Hewitt, and Geoff Hoon in a sting operation. Stephen Byers, former Secretary of State for Transport, described himself as a ‘cab for hire’ to journalists pretending to represent a lobbying firm. This sting operation came hot on the heels of The Daily Telegraph’s publication of the MPs expenses scandal in 2009 when it emerged that a large number of MPs from across the political spectrum had fiddled their expenses prompting Gordon Brown to apologise on behalf of all politicians. It was looking as if the ‘bad apple’ analogy could no longer hold in the face of evidence of a ‘Rotten Parliament’.

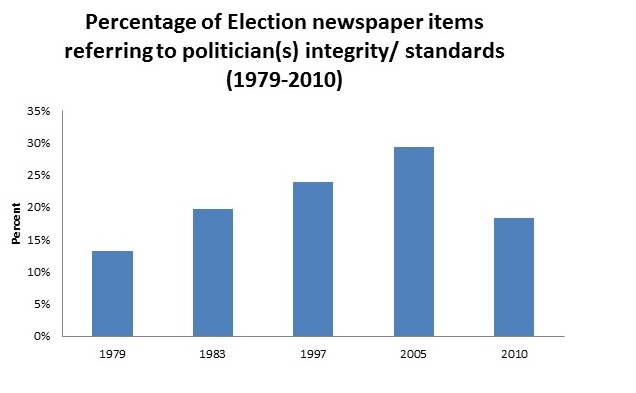

Possibly because the expenses scandal was so widespread, potentially damaging and cross-party in nature the issue received relatively little attention in the 2010 General Election in comparison to 1997 and 2005. There were, of course, major economic and political issues to debate besides sleaze but it was clear that none of the major parties (taking on board Tony Blair’s words of wisdom about precipitating the suicide of the political elite) wished to dwell on a subject that would make them all look bad.

Source: Deacon, D. and E. Harmer (2014) Changes in UK General Election Newspaper Coverage (1918-2010), End of Project Report for Leverhulme Trust, Loughborough: Loughborough Communication Research Centre

This ‘conspiracy of silence’, however, did little to diminish the spread of the idea that politicians are self-serving. The relatively good performance of the Liberal Democrats in the 2010 General Election was based on the idea that they had not previously been in government and were, amongst other benefits, not tainted by so many scandals. This, of course, is no longer true (the Liberal Democrats association with convicted fraudster Michael Brown was the biggest of a number of party scandals).This increasing distrust of ‘the Establishment’, together with the economic consequences of the financial crisis and public concerns about the levels of immigration that neither the Brown government nor the Cameron-Clegg coalition could master, has led to growing support for minor parties such as UKIP and the Greens.

Return of the Sting?

This brings us to consider how big an issue corruption will be at the 2015 General Election. Is it still an issue that the parties would wish to skate over or will it gain media attention? Judging by what we have seen so far (and some speculation on our part) there are reasons to believe that corruption will be bigger at this Election than in 2010, which may for some be counter-intuitive given the proximity of the expenses scandal to the 2010 General Election. Why?

The UKIP factor?

We have UKIP which is avowedly anti-Establishment and can potentially win votes by dwelling on the records of the major political parties. The major political parties, on the other hand, are eager to discredit UKIP and one way to do this is to reveal the extent of corruption in that party. Indeed it is likely that they will focus their attack on the misdemeanours of UKIP candidates rather than take issue with UKIP policies particularly on immigration as this issue is seen as a vote-loser by both Conservative and Labour leaderships.

A Flurry of Finger Pointing

In addition, we have a Labour leader who has broken the ‘conspiracy of silence’ and is seeking to distinguish himself from both the sleaze of New Labour and the Conservative Party by stressing his honesty and trustworthiness in comparison to David Cameron and his close involvement with Andy Coulson and others engaged in tax avoidance activities. The Conservatives have responded by delving into the personal financial affairs of Ed Miliband and the changing of his father’s will allegedly in order to reduce inheritance tax. So far in the run-up to the General Election we have the deja vu Straw and Rifkind ‘cash for access’ sting from C4 Dispatches, which both parties sought to bury as quickly as possible but we have also The Sun’s sting on Janice Atkinson, a prominent UKIPer, for fiddling European Parliament expenses, The Mirror’s sting on Afzal Amin and his shenanigans with the EDL and The Sunday Mirror’s classic honeypot sting of Minister for Civil Society Brooks Newark.

Regulating Press Standards

The fact that the controversial Independent Press Standards Organisation has recently cleared The Sunday Mirror of any wrong doing should serve to embolden the press in this matter. In a defensive mode parties will be unceremoniously ditching the ‘bad apples’ to ward off accusations of broader corruption. In attack mode, the parties and their respective supporters in the media seem to think for the moment at least that there is political capital to be made from corruption. Whether this will continue as the campaign proper unfurls, time will tell.