CRCC members co-publish book with the European Election Monitoring Center on Party Campaigning in European Parliamentary Elections 1979-2019

The Political Communication theme is delighted to announce the publication of a timely new book by members Dominic Wring and Nathan Ritchie(eds.) Europe Votes: Party Campaigning in European Parliamentary Elections 1979-2019, a joint venture involving the European Election Monitoring Center and ourselves which is now free to download from its own dedicated website https://www.europevotesbook.com

This book offers a comprehensive look back at how political campaigning has evolved in the second largest democracy (after India) of 400 million citizens – and does so as member states go to polls next month for the tenth European elections. Europe Votes features twenty experts analysing developments in their own countries from, where applicable, the inaugural elections of 1979 to the most recent ones in 2019. The Foreword to the collection has been kindly provided by Joyce Quin, a former Member of the Brussels and Westminster Parliaments, who was the UK Minister for Europe and currently sits in the House of Lords. In her contribution, Baroness Quin reflects on her formative experiences as a successful candidate in the first European elections and her subsequent career as a politician in the only member state to have left the European Union.

Every chapter of Europe Votes features content from the European Elections Monitoring Center archive which holds more than 15000 campaign items. This unique collection of material, compiled by the EEMC with support from the EU, is now available to consult online. The archive includes items from each of the previous European elections, every member state that has participated, and from the political parties that have secured most parliamentary representation. Europe Votes focuses on nine selected countries: the so-called ‘big four’ of France, Germany, Italy and the UK, and five members- Greece, Spain, Sweden, the Czech Republic and Hungary- that joined (in that stated order) during one of the subsequent waves of European enlargement. An additional chapter revisits the Brexit controversy through an examination of the final European elections held in the UK on the eve of the country’s departure from the EU.

Europe Votes considers specific developments in the member states with chapters offering insights into successive European election campaigns in the featured countries. There are, however, some common themes that emerge. For instance, the three mainstream EU party groupings – conservative, social democrat and liberal – have been quite electorally resilient despite growing challenges from the Greens and more recently the various Eurosceptic forces. The latter may have been increasingly effective in promoting their case to the electorate but rivalries involving the United Kingdom Independence Party, Alternative for Germany, French National Front, and Lega in Italy – plus an assortment of likeminded politicians in other countries – has so far tempered these parties’ ability to exert more concerted influence within the European Parliament. The 2024 elections may of course change this situation.

Growing criticism of the EU has been a marked feature of successive European elections. Several contributions touch on this, with the Italian chapter making telling reference to what is termed ‘strategic Euroscepticism’. This phenomenon can be observed when politicians adopt anti-EU messaging during campaigns but subsequently moderate their positions once elected. Two striking examples of this documented by Europe Votes are the France and Sweden cases where some of the most strident campaigners have muted their previously expressed support for ‘Frexit’ and ‘Swexit’ respectively.

Europe Votes incorporates material from the EEMC archives to illustrate some of the most important issues, parties, and personalities that have defined the various campaigns held over forty years. Examples of this in the book include:

- cultural icons- in the form of flags and mythological figures such as France’s Marianne (1992), a figure in traditional Greek dress (2009) and the parties wanting to secede from Spain (and other states) while remaining within the EU (2019)

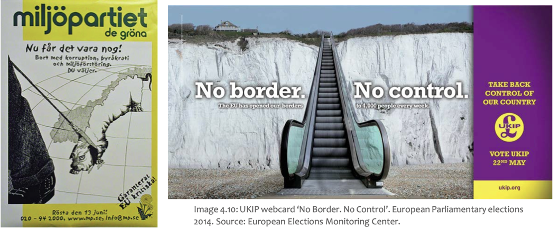

- sovereign nations- the Swedish Greens use their country’s physical shape to make a sceptical point (1999) while UKIP draw on the iconic southern English cliffs of Dover to promote their ‘Take Back’ slogan (2014), a message that would gain notoriety two years later in the country’s EU Referendum

- European (dis)integration- while the Italian Lega warns that EU immigration policy could subjugate native populations (2009), the Czech SPD features prominent allies from other countries to help amplify its sceptical message (2019)

- The Euro- or more precisely its critics who, literally from left to right, include the Greek Communists (2004) and Alternative for Deutschland (2014)

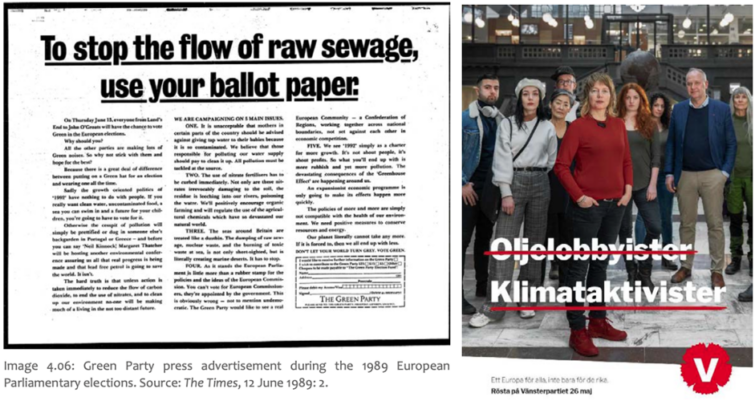

- Environmental concerns- the UK Greens’ surge (1989) has contemporary resonance while the Swedish Left Party promotes climate activists and simultaneously denounces oil lobbyists (2019).

- Yes to EU- even the most Eurosceptic countries have politicians who are prepared to champion the European Union such as the Hungarian (2014) and UK (2019) oppositions, that latter of which makes a popular cultural reference to the 1970s era in which Britain originally joined the then European Economic Community