Corbyn, Labour, Digital Media, and the 2017 UK Election

Labour did not win the general election. But neither did the Conservatives. Parliamentary arithmetic will prevail and the Tories will form a minority government propped up by the hard-right DUP. Will there be a hard Brexit? Will austerity continue along its previous punishing trajectory? Who knows, but both seem less likely with a minority government. Will the government even last until the autumn?

This is a picture of Jeremy Corbyn addressing a crowd in Gateshead.

We never pulled crowds like this in 1997. #GE2017 pic.twitter.com/YsWPi7z7Lk— John Prescott (@johnprescott) 5 June 2017

The result was truly extraordinary and begs so many questions but here I want to discuss how Jeremy Corbyn and his movement of activists are changing the Labour party.

Labour’s share of the vote saw a huge increase. The party picked up seats in constituencies, such as Canterbury (Tory since the First World War) and Kensington, that nobody would have predicted would switch to Labour, and certainly not Corbyn’s Labour. Five weeks ago, Labour were lagging behind by about 20 percent in most opinion polls and there were forecasts of a 150 seat majority for the Conservatives. This is, after all, why Theresa May called the snap election in the first place. After the election that gap stands at only 2 percent, with Labour on 40 percent and the Tories just north of 42 percent.

UKIP’s share of the popular vote has been slashed to just 1.8 percent, against a 2015 total of 10.8 percent. Across the country, but particularly in places like the north east of England UKIP were crushed as voters switched back to Labour as well as the Conservatives. UKIP’s much vaunted “threat” to Labour in working-class constituencies like Hartlepool or Middlesbrough, for example, repeated in broadcast media vox-pops with “ordinary voters” over the last few weeks, melted away like snowflakes in the sun.

It turned out these were not representative of “ordinary voters” but, as we know from decades of journalism research, they were editorially selected because they fitted with the “Labour is failing” frame. Labour saw off the challenge and increased its share of the vote in the areas where UKIP was supposedly going to split the Labour vote and hand seats to other parties. Labour trounced UKIP in Wales. The results in London show just how strong Labour has become in Britain’s capital. And, yes there was a remarkable Tory recovery in Scotland but Labour also won seats north of the border.

June 9 was huge for Corbyn and the movement of new party members that sustained him through his election as Labour leader in 2015 and the challenge to his leadership last year.

Shifts in Engagement

The deep question here is to what extent Labour’s surge during the campaign — and remember it was really only during the final two weeks of the campaign that the surge became evident — can be explained by broader, below-the-radar, systemic shifts in political engagement in UK party politics and how elections are being reshaped by ongoing changes in our media system.

Central to this are new forms of engagement through digital media and how they jell with both the evolving ground war on the doorstep and online, as well as longer-term cultural shifts in how people experience politics. As Jenny Stromer-Galley and I argued last summer in a think piece that served as the introduction to a special issue of the International Journal of Press/Politics we edited on digital media, power, and democracy in parties and election campaigns we edited, the growth of digital media in citizens’ political repertoires has affinities with a broader shift toward youth engagement, and a general skepticism of authority. There is a willingness among many individuals to see elections and party participation as fair game for social media-fuelled contentious politics of the kinds that have been so important for non-party protests and mobilizations over the last decade. This is happening among those significant sections of the public who have started to channel their social media-enabled activism into party politics and to integrate it with face-to-face doorstep campaigning under the guidance of the new Labour party leadership and Corbyn’s ancillary movement Momentum.

We saw similar forces at work with Bernie Sanders’ campaign in last year’s U.S. presidential election. We saw it with Italy’s M5S and Spain’s Podemos. Key here is the process of organizational and generational cultural changeand how it fits with changes in how digital media are now used in political activity.

When Labour lost the 2010 election, and even as Corbyn continued to attract a huge influx of new members for his party during 2015 and 2016, much commentary revolved around the “death” of social democracy and even the party form itself. But what June 9 suggests is that, for Labour and its half a million-plus members, the party organizational form is alive and kicking.

Rather than dissolving, Labour looks like it is going through a long-term process of adaptation to postmaterial political culture and is leading the way in new organizational strategies that combine online and offline citizen activism. Skepticism about Labour’s new members, suggesting that they are not prepared to help out on the doorstep and are merely “clicktivists” who don’t see the value of old-style campaigning now seems wide of the mark.

This is a complex process. Interactions between the organizations, norms, and rules of electoral politics, the new, flexible, ad hoc, connective styles of political engagement, specific issues, and the affordances and uses of digital media will make the difference. National, regional, and local contexts will also shape overall outcomes.

Digital Media and the Party-as-Movement Mentality

But still, digital media foster cultures of organizational experimentation and a party-as-movement mentality that enable many individuals to reject norms of hierarchical discipline and habitual partisan loyalty. This context readily accommodates populist appeals and angry protest — on the right as well as the left. Substantial numbers of the politically active now see election campaigns as another opportunity for personalized, contentious political expression and for spreading the word in their online and face to face networks. As a result, Labour is being renewed from the outside in, as digitally enabled citizens, many (though not all) of them young people, have breathed new life into an old form by partly remaking it in their own participatory image. The overall outcome might prove more positive for democratic engagement and the decentralization of political power than many have assumed.

So far, this shift has not touched the Conservatives. They remain a declining party, with a shrinking membership of fewer than 150,000, stuck in the elite-driven, broadcast-era mode that they (and Labour) perfected a generation ago, bolting on digital media targeting without the engagement.

Turnout among young voters rose significantly during this election. A reported 63 percent of 18–34 year olds voted Labour. The campaign saw a massive voter registration drive led by Labour, the Liberal Democrats, and the Greens, but missed in the coverage is that the parties were also joined by online movement 38 Degrees who ran their own crowdfunded registration campaign including targeted Facebook advertising that generated four million “register to vote” ad viewings. It looks like it worked.

Yet The Right-Wing Press Still Matters

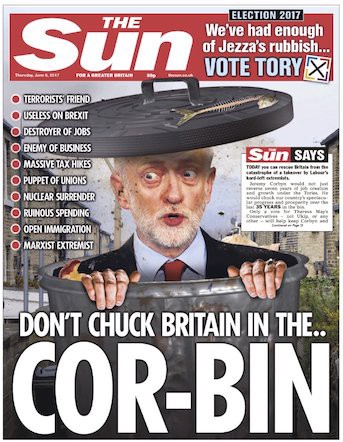

At the same time, it pays to remember that these extraordinary changes are also accompanied by persistent, long-term trends in our media system. Today some commentators are claiming that the power of Britain’s overwhelmingly right-wing tabloid media is on the wane. The election day front pages of the Sun, the Star, the Mail and the Express were outrageous even by the usual standard of these outlets, leading some to suggest that these news organizations protested too much and failed to influence the outcome of the election. There is a new alternative news ecosystem emerging in UK politics, with sites like The Canary (6m visits a month) generating much shareable content that has been used to foster solidarity among those young Corbyn supporting activists.

But we need to remember that the Conservatives achieved more than 42 percent of the popular vote and will be forming a government, albeit a weak one. Labour surged, against all the odds, but it seems difficult to suggest that the incessant campaign against Corbyn in the British press did not make a difference to the overall outcome of the campaign.

How long the Conservative-DUP minority government will last is anyone’s guess. But there are deeper changes underway on the British left. Digital media logics, in complex interactions with older media logics, older organizational forms, and evolving patterns of participation are playing a role in these changes.

Andrew Chadwick

Prof @newpolcom. From August 2017 I’m moving to be Prof @lboroCRCC & @lboroSocSci. http://www.andrewchadwick.com