Assessment and feedback – developing new solutions to an old problem

Jisc’s Assessment and Feedback Programme has been exploring ways in which technology can be used to address student dissatisfaction with feedback and assessment. Ros Smith, drawing upon this work, identifies four common problem areas, providing examples of interventions being developed to address each (Smith’s original blog post can be accessed here).

Problem 1

“assessment and feedback is by and large devolved to individual curriculum areas, making it hard for institutions to provide a consistent assessment experience and harder still to implement on any scale the enhancements technology can bring.”

Smith advocates a two pronged approach – firstly, identification of the principles underpinning effective assessment and feedback. Secondly, introduction of institutional strategies based on these identified principles to act as a clear set of guidelines against which Schools, departments and module leaders can refer.

Problem 2

“In a modular system, assessments tend to occur at the end of modules, with little scope for putting feedback into practice.”

In 2011 the University of Dundee instituted “an online, self-evaluative feedback/feed forward process” (1) as part of their medical education programme. Using pre-existing technologies students downloaded a cover sheet from the virtual learning environment (VLE) prior to submission wherein they made explicit how previous feedback had informed their current work. They were also provided an opportunity to request specific feedback from their tutors. On receipt of their marked assignment students were prompted to upload their work to a personal wiki in which they could reflect on the feedback received. Accessible by both the student and tutor, the wiki facilitated on-going dialogue between both parties and acted as a record of progress.

Problem 3

“Assignment bunching…means learners can end up taking several high-stakes assessments simultaneously if modules come to a close at the same time…with limited opportunities for sharing and reflecting on feedback, it is no surprise that understanding how to improve gets put on the back burner.”

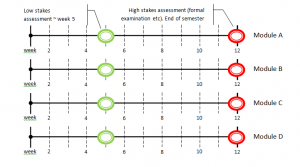

Assessment timelines (developed by the University of Herefordshire) looks to counteract “assignment bunching” by encouraging staff to consider assessments on a programme, rather than module, level. Adapted from a 2010 paper by Mark Russell, consider the following example:

Russell refers to this as a “typical example of assessment”, with each timeline representing a module on the same programme. Similarly weighted assessments are due in the same weeks across all four modules, with the heaviest weighting assessment occurring at the end of each module in a summative essay or exam piece. Compare and contrast this with the alternative assessment configuration below:

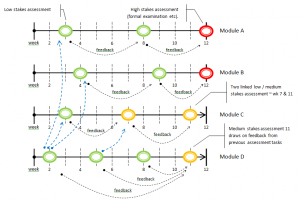

So what would be the benefits of adopting the second approach?

- A more even work load (for both students and staff).

- Less assignment bunching – students can more fully engage with each assessment.

- Assessments are linked by feedback – the shift to a more formative style of assessment allows for feedback to be more easily put into practice.

- Modules are linked by feedback – relationships between modules are made explicit, with skills relevant to one module understood as relevant to another.

Problem 4

“The valuable contribution learners could make to improving assessment and feedback is underused. Even though learners can offer powerful insights into what works and what doesn’t, few institutions involve them in assessment and feedback design.”

FASTECH (Feedback and Assessment for Student with Technology), a student fellow scheme developed by the University of Winchester and Bath Spa University aims to “engage students as partners in embedding technology-enhanced assessment-for-learning practices across all programmes of learning” (1). The scheme see “students working as equal partners with academic staff” (3) in proposing, gathering evidence and evaluating ways of “enhancing the student experience of assessment and feedback…acting as advocates for the use of technology-supported approaches whenever these offer proven learning gains” (1). This collaborative approach not only facilitates communication between students and academics but produces the kind of “robust evidence” (4) needed to “convince uncommitted staff” (5) of the benefits of adopting “technology-enabled practices” (5). Since the schemes inception a “greater incidence of effective technology use and a wider range of assessment tasks” has been in evidence across both institutions, “from online exemplar marking and online peer review to video self-assessment” (5).